|

|

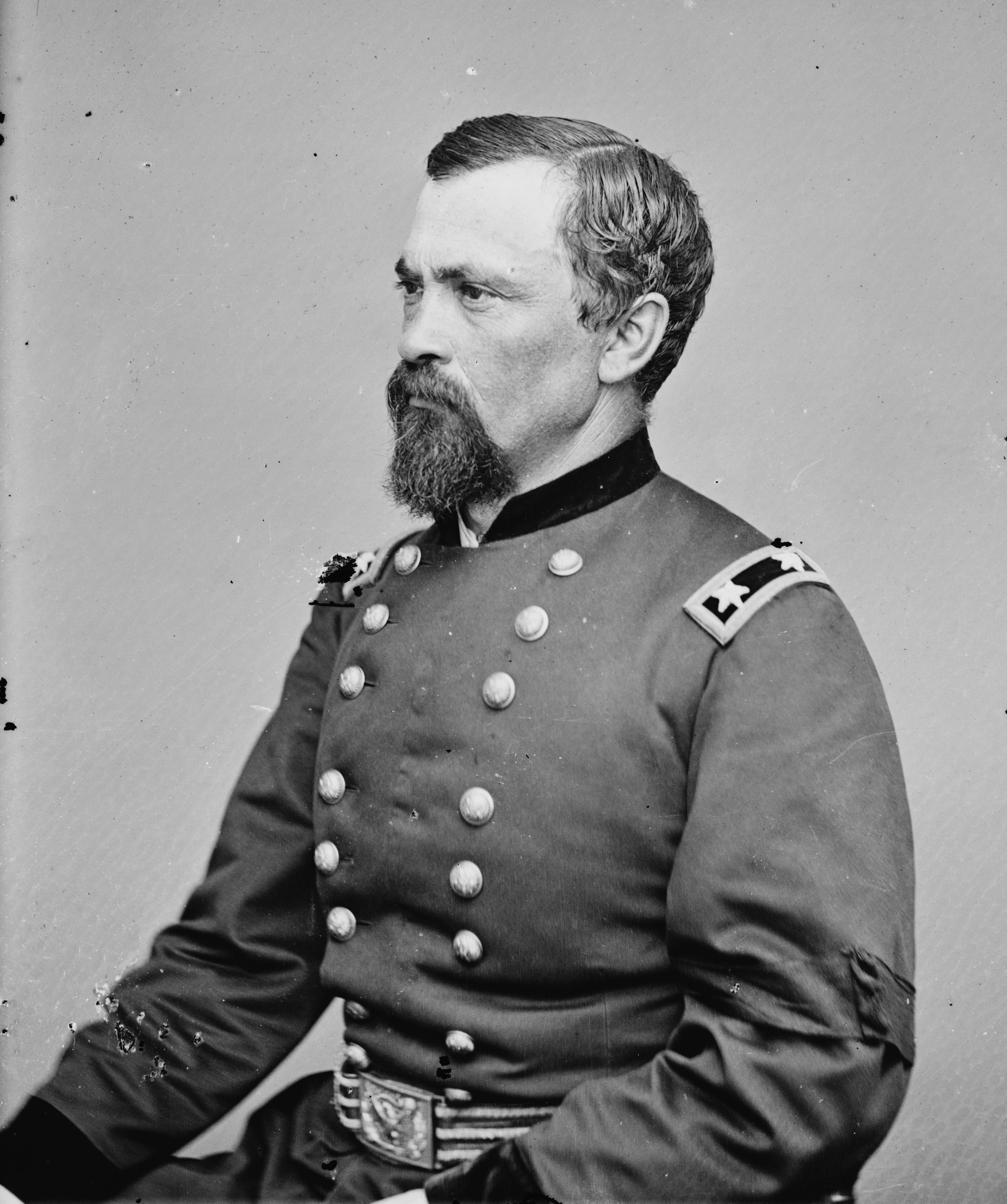

Lt. August V. Kautz For more on Kautz, see Rodney Glisan's Journal of Army Life. The howitzer from Fort Vancouver, accompanied by Lieutenant Kautz and six men, arrived here Friday evening, en route for Rogue River. It is a brass twelve-pounder, and calculated for the throwing of shell. They have also grape and cannister. Oregon Statesman, Salem, August 30, 1853, page 2 CAMP ALDEN, Rogue River, O.T.

Sir:--I have the honor to report to you

of my

safe arrival at this camp today, with the greater part of the

ammunition and the gun, and take great pleasure in acknowledging the

obligation I am under for the assistance you have afforded me through

Capt. Nesmith and his company, without which it would have been utterly

impossible for me to have gone through in the comparatively short time

that I did, and had I been left entirely to my own limited resources, I

do not think that I could have got through at all. The Captain was

necessarily much detained by his instructions to remain with the gun,

and the detention was increased by the bad weather. Had it not have

rained, we would have reached our destination in ten days from Salem.

It was an arduous task to get the carriages along, and frequently

required the twelve mules and all the men that could get round to get

one of the wagons up the hills. The men did exceeding good service, and

for four days were constantly at the wheel. In the Canyon, they were

for the greater part of two days in mud and water, and quite a number

of the men were afterwards taken sick in consequence of the exposure

thus incurred. Captain Nesmith himself was foremost at the wheel, and

his example did much toward contenting the men with their hardships,

and everything toward getting the gun through. Nothing has occurred

since we started requiring the use of the gun here, except perhaps the

moral effect of its presence upon the Indians, in which Gen. Lane seems

to have great confidence, and he has expressed himself exceedingly well

pleased with its arrival. With many thanks for your kindness and

renewed acknowledgment of my obligations, I remain with great respect,Sept. 9th, 1853. Your obedient

servant,

To Hon. George L. Curry,AUGUST V. KAUTZ, 2nd Lt., 4th Infantry Acting Governor, O.T., Salem, O.T. Oregon Statesman, Salem, September 27, 1853, page 1 INTERESTING FROM OREGON TERRITORY.

Our Fort Lane Correspondence. Fort

Lane (O.T.), Sept. 29, 1853.

Termination

of the Rogue River War--History of the Campaign--Origin of the

Strife--Character of the Rogue River Indians--Defeats of the

Whites--Arrival of General Lane--Battle of Evans Creek--Massacre of the

"Grave Creeks"--Their History--The Taylor Slaughters--Last Battle Since

the Treaty--Its Stipulations--The Bearded Chief--Departure of General

Lane for Washington.

The

Rogue River War having, like all other wars heretofore, come to an end,

it becomes the part of an impartial historian like myself to transmit

to posterity a true record of the glorious deeds performed in the short

but brilliant campaign so nobly begun. I doubt whether anyone has had

the generosity to give honor to whom honor is due, and it is to rectify

any partial statement that may have gone abroad of the heroisms enacted

in this valley that I send you this brief but impartial synopsis.It taxes the ingenuity of the inhabitants of this valley to the utmost to assign a cause and a commencement to the sanguinary conflict. Each individual has his own story of how and where the war first began, and though all aim to, none succeed in fixing the commencement of hostilities upon the Indians. Last winter seven successful miners down on Rogue River, near Galice Creek, were murdered by the Indians, it is supposed, and a large amount of gold dust is thought to have fallen into the hands of the murderers. There is no positive proof that the deed was committed by the Indians, but they were immediately charged with it, and the desire to recover the captured treasure, rather than to revenge the murder, set on foot many desperate expeditions composed of reckless and abandoned men. John [sic] Taylor was the chief of the Taylor Indians in that vicinity. He was caught last spring, tried and shot. Before his death he is said to have confessed to the massacre, and to have implicated quite a number of his own people, and two of the Grave Creek Indians also. The latter, as well as quite a number of the former, were brought to death, but no outbreak followed these troubles. For some years a rumor has existed that a white woman had been captured and her husband killed by the Indians of this valley, about seven years ago, and that she had been kept in bondage by them ever since, in the mountains, out of sight of the whites. Last summer an Indian came to Jacksonville and gave a fresh impulse to the rumor. He stated that the woman had long persuaded him to go and report her bondage to the whites, and that he had finally consented to do so, and if the whites would go with him he would show them to the Indian camp where she was a prisoner. A party of eight or ten white men joined in the expedition, and, guided by the Indian, after some trouble came upon the Indian camp in the mountains where she was said to be kept a prisoner. They positively denied the story of the white woman, but admitted a similar one with regard to a foreign squaw captured from a half-breed Spaniard. She was brought, and proved to be a Klamath Indian woman. The white men considered this a subterfuge, and insisted on having the white woman given up, or they would kill them all. The Indians became alarmed and endeavored to make their escape; the white men fired upon them and killed six of them. No outbreak followed this affair, though it is said to have had a serious influence upon the war. The following having preceded the outbreak but a very short time--one or two days only--is most generally regarded as the immediate commencement of hostilities. Last summer a Spaniard and gambler in Jacksonville, by the name of De Bushay, bought a squaw of Jim, one of the chiefs of this valley. The squaw was the widow of a Shasta Indian, and had returned to her people. Her husband's brother claimed her as his property. De Bushay having failed to comply with the purchase, Jim stole her away from him. De Bushay raised a party, and by threats and arms recaptured her. The Shasta Indians, who had come for her, were witnesses to her forcible abduction, and were highly incensed. They went away threatening vengeance on the whites. In a short time afterwards Edwards, Gibbs and others were killed under circumstances that struck terror into the hearts of the people of Jacksonville. A perfect stampede followed. The inhabitants, without reflection, concluded that a league had been formed against them by all the Indians in the country, and the war commenced. The whites began the campaign by killing all the pet Indians about town--a term applied to Indians engaged in families in a domestic capacity, and necessarily perfectly innocent of any part whatever in these murders. They then extended operations against the Indians employed in families in the country, and any master who protested against the hanging of his servant was threatened with a similar fate, and thus these brave men went scouring about the country, killing and hanging these inoffensive creatures, instead of following the real perpetrators into their mountain haunts. A little boy, practicing with his bow and arrow on the plain, was thus disposed of. An old man and woman have met with similar fates. No matter how peaceably disposed the Indian might be, he was either killed or driven to the mountains in self-defense. The Rogue River Indian is brave, and will resist when imposed upon or mistreated, and will endure no maltreatment submissively. These Indians have never been friendly to the whites, from the earliest traveling by them through this country. Up to 1850 scarcely a party passed through the valley without experiencing some depredation from them. They have ever been jealous of the encroachments of the white men, and never were at peace with them until Gen. Lane concluded a treaty with them in 1850, which they faithfully adhered to until broken by the whites. They are noted for their truthfulness. Joe, Sam and Jim are the principal men amongst them. Until the inconsiderate and base retaliation of the whites, neither these chiefs nor their people took any part in the outbreak, nor had they done anything to justify the mean attack upon their people. But, driven by these acts to self-defense they fought with desperation, for the whites threatened them with extermination. They went to war with a magnanimity unknown among savages. It is true they waylaid the roads, burnt houses and grain, and carried their depredations almost into the streets of Jacksonville. But there was no scalping, no killing of women and children. The whites were terror-stricken at the boldness of their acts. The fact immediately forced itself upon their minds that the Indians had by an illicit and abandoned trade on the part of the whites obtained possession of nearly all the arms in the country; the whole country flocked to Jacksonville, and the town was thronged with unarmed and helpless men. Expresses were sent off to every direction for aid, but before it could arrive much damage had been done, the farms and dwellings of industrious farmers had been laid waste, and many valuable lives were lost by a war brought on by desperate and unprincipled miners, gamblers and outlaws. The whites for some time were driven in on every quarter. About the 15th of August Griffin's party of twenty men was driven in with the loss of a man. On the 17th Lieutenant Ely lost nine men killed and wounded, and though reinforced did not think it prudent to pursue the enemy, though they had withdrawn. It was not until the arrival of Gen. Lane that the whites began to triumph. On the 24th he brought the Indians to terms. Of this fight much has been said and published that is calculated to convey a wrong impression. A party of ninety men under Gen. Lane, Capt. Alden, U.S.A., and Capt. Armstrong of Yamhill surprised the Indians on the headwaters of Evans Creek. The position of the Indians was very strong, at the head of a defile or bayou, behind a belt of fallen timber that extended across the defile. In the early part of the action Gen. Lane ordered a charge, in order to drive the Indians out of the brush. To this order Capt. Alden and his ten regular soldiers, Capt. Armstrong and a few others alone responded. Capt. Armstrong was killed instantly--shot through the right breast. Capt. Alden received a dangerous and remarkable wound; the ball entered the neck, and passing between the jugular vein and windpipe, came out under the right shoulder. Gen. Lane was shot through the right arm, near the shoulder joint. Thus all the officers who led the charge were shot down in the early part of the action, in consequence of not being supported. For three or four hours the firing was kept up from behind the trees, Indian fashion, and finally the Indians proposed to "wawa" (talk). General Lane opposed it, and wished to continue the fight, but the men urged an armistice--a vote was taken, and nearly all decided for a parley. The armistice was barely entered into when Colonel Ross arrived with a reinforcement of one hundred and twenty men. This reinforcement raised the valor of some of the men, and they wished to renew the fight. The General consented, but said that he must send Joe and Sam word to say that the parley was ended. To this they would not consent, and the General then said they must abide by the treaty, and so they did. Twenty minutes after the firing ceased, whites and Indians were mixed up in the same camp in the most admirable confusion. The squaws carried water for the whites, who were suffering from thirst, and the Indians offered to carry in the wounded to where they could be attended. The Indians were to come in in seven days to enter upon a treaty of peace and the sale of their land. But before the treaty could be entered into, other circumstances occurred that deterred the Indians from coming in at the appointed time. If they did not come in, the war was to be renewed. Gen. Lane thought the Indians were excusable in not coming in; some of his men thought otherwise, and were for renewing the war. The reader may form his own opinion from the following facts, unprecedented in the history of American wars: The emigration of '46 was the first that ever passed by the southern route into the Willamette Valley. An account of the origin of this route may be found in Thornton's Notes on Oregon and California. A small party of that emigration encamped on a clear, beautiful little trout stream, about forty miles from where Jacksonville now stands, down Rogue River. Miss Crowley, a member of this party--a young and interesting girl--had, in spite of her frailty and the hardship of emigration, succeeded in getting thus far on her way in search of a home in the Far West. But, a victim to consumption, here, amid the bold hills that are the almost unerring characteristic of this mountainous country, she breathed her last, and under the shade of an oak, not fifty yards from where Bates and Twogood now keep, they buried her, and called the creek that flows nearby Grave Creek. Her remains were dug up by the Indians as soon as her friends left the grave, and though passing strangers buried them again and again, yet they were as often removed, and no one has ever passed by and found the grave closed until the affair I am going to relate closed it up forever. A party of Indians, formerly thirty or forty in number, but since reduced to ten or eleven, have owned and claimed this valley from the time it was first known to the whites, and have, since the naming of the creek, been called the Grave Creek Indians. They were an outcast band, made up of the outlaws of all the other tribes in this country. In early times, when the country was only visited by trappers, they were a great annoyance to the people sent out in that capacity by the Hudson Bay Company. When the emigration took this direction they were a terror to all small parties, killing and stealing the cattle where they feared to attack the men, and this constant war so reduced their numbers that they had but eleven warriors previous to this outbreak. Tyee Bill and another of their party were implicated by the confession of John [sic] Taylor. Bates raised a party of whites, and, guided by his pet Indian--also a Grave Creek--he came upon them in the mountains and succeeded in capturing all of them except Tyee Bill. The implicated Indian was hung, and the others released on condition that Tyee Bill should be given up. His head was brought in soon after. A treaty was then entered into by Bates with these Indians: he was to protect them, and they were to disturb the whites no more. They came and settled near him, and were quietly and peaceably disposed, when a man by the name of Owens infringed upon the treaty by wantonly shooting one of them one day as he was passing, having occasion to discharge his gun. Owens is a miner, but has had sufficient influence among a set of his own stamp to raise a company of thirty men. In the interval between the death of this Indian and the outbreak at Jacksonville, a house on Louse Creek was burnt, and the bodies of its two inhabitants were found in the smoldering ruins. As the Grave Creeks had moved away from Bates, they were charged with this affair, as it occurred only twelve miles from Bates' stand. Either they were not guilty, or to lull suspicion perhaps they returned and encamped near Bates again. Bates and his party, under pledges of friendship and protection, succeeded in taking four of the remaining eight Grave Creeks prisoners. Owens raised his company of thirty men immediately on the alarm at Jacksonville, and came down to Grave Creek on the same day, and soon after Bates had taken these four prisoners. He immediately took the matter into his own hands. He sent his men up, surrounded the Indian camp, and shot the only Indian in it--the other three were out hunting. Their return was patiently awaited, and as they came in with their game upon their backs they were fired upon; one was killed, and the other two ran away, though supposed to be wounded. They uttered the war cry as they escaped, and then communicated the state of affairs to the prisoners in Bates' house. One of them burst his bonds, and, seizing a shovel, attacked the guard, and severely injured a man by the name of Frazelle on the hand. Frazelle finally shot him through the body with a revolver. The other three were shot, tied as they were, among them Bates' pet, who had been in his employ all summer. The six dead Indians were then thrown into the open grave where Miss Crowley was buried, and covered up, and as they were undoubtedly the desecrators of her tomb, it is closed forever, and they have had the satisfaction that is allowed to few--of digging their own graves. A man by the name of Adams, one of the participators, bought a little boy of ten years, for $50, from one of Owens' men, and has taken him into Willamette Valley. The women made their escape that night, and they, as well as the two Indians who escaped, have not been heard of since. This is the story of the Grave Creeks, as I heard it from Bates and Twogood, and others. Whilst I stopped at Bates' a man by the name of Johnson was pointed out to me as the leader in this affair. He was a very unprepossessing person, slovenly dressed in an old hickory shirt and ragged pantaloons, and shoes without socks. His old slouched hat concealed the principal part of his unshaven countenance; either his eyebrows protruded very much, or his cold gray eyes were sunk very deep in his head--I could not tell which. Without passion, without expression in his dark features, he stood with his hands in his pockets and his back braced against the wall, and told his story: News of the outbreak at Jacksonville reached the mines on Illinois River, twenty or thirty miles below Bates', and they immediately "forted up" at Johnson's house, on Rogue River. About thirty white men were collected there, and, directed by Johnson, they convened about twenty-five warriors of the Taylor Indians at their fort, under pretense of making a treaty with them. They gave them plenty to eat, and, to lull suspicion, the whites had concealed their arms under the beds in the fort. When they were all busily eating about the fires between the fort and the river, they fell upon them, and eighteen out of the twenty-five were killed. These are the simple facts, as related by Johnson. He did not enter into particulars. I asked him if they had done damage below, and it appeared that they had not participated in the outbreak at all, but it was feared they would, so they killed them. John Taylor had a son named Jim, who separated himself from his father's people, and had joined the Indians on Applegate Creek, headed by Old Man John. Previous to the conclusion of the treaty Capt. Bob Williams with his company was sent to hunt up the Indians on this creek and bring them to an engagement. Williams is a man very much after Capt. Owens' stamp, but has also the reputation of being a great Indian fighter. As soon as the treaty was concluded General Lane sent an order to Capt. W. to report himself at headquarters. For some reason the order never reached him. A second order was sent, but the bearer was bribed by the opponents of the treaty not to deliver it. Williams continued in the mountains notwithstanding that the treaty was concluded, a fact that he knew, though he may not have known it officially, for he was in daily communication with Halstead's ferry, where the disbanded troops were every day passing with the news. Meanwhile the Indians were making every effort to get on the north side of Rogue River, to General Lane's headquarters, to be present at the treaty. Finally the Indians brought the news that Williams had killed Jim Taylor. Their account made it an infamous affair. Williams had an interpreter and guide, who passed by the sobriquet of Elick, who knows the country and the Indians, and is conversant with their tongue--he is a half-breed. With his assistance they found the Indians, but could not get at them; they were high up on a mountainside, and Williams was in the valley. Elick represented the party as miners, that they come from General Lane with power to treat with them, that they wanted them to come down and do so, so that they could go to work, and they might carry on the war with all other whites if they chose. They offered them plenty to eat, but the Indians were cautious and would not come down; they knew the fate of the Grave Creeks. For many hours they parleyed, but finding they could not be induced to come down, they desired that a part might come, and then they asked that three should come, and finally they entreated that one man might be sent to treat with them. Their entreaties were so earnest and kept up for so long a time that at the length Jim Taylor yielded. He came down and was instantly seized and carried off to Halstead's ferry, where they went through the form of a trial and tried to convict him of some of the injuries done to the whites, but nothing could be proved against him. He was then threatened with death if he did not confess to the part he had taken in the war. He admitted nothing, and was condemned to be shot. They took him into the woods below the ferry and tied a rope about his neck and fastened it to the limb of a tree above his head. Five men were selected who fired upon him, two balls passed through his head and the others entered his back. His body was left dangling to the limb. An old man from the Willamette by the name of Yates was at the ferry, but would not go down to witness the deed, but after they came back he proposed to burying him, but no one would volunteer to assist him until finally two men went with him and dug a grave for the dead Indian, and placing his scalp--which some white man had taken off in the meantime and hung upon the bushes--on his head again, they buried him. Finally Old Man John succeeded in dodging Williams; he got across the river and was present at the signing of the treaty, and received his first payment. He reported all his warriors present but five, though quite a number of his women and children were still about. On the 15th of September Williams returned and reported that he had had a desperate battle on the 13th. He had found the Indians in the bush and attacked them, and after four hours fighting night came on and interrupted the conflict. He had killed and wounded twelve Indians and had but one man killed. The news of the fight reached camp through the whites before the Indians knew it. It was told to John, and he was asked if they were his people; he said no, they could not be his, as they were all present but five, that it must have been Tipsu Tyee's band. On the evening of the 15th John's five men presented themselves to Gov. Lane and told their story. They had been attacked by Williams as they were endeavoring to get across the river on to the reserve, with the women and children. They had but three guns, and with these they kept them at bay until night, when they made their escape. They lost one woman and two children killed. This is the last battle with the Rogue River Indians fought by Capt. Williams. Owing to these contradictory transactions, the treaty was pending about three weeks before it could be concluded. In the meantime, many volunteers had flocked in, eager for the contest. Disappointed with no prospect for a fight, much dissatisfaction was expressed at the state of affairs. Gov. Lane, having full confidence in the good will of the Indians, discharged all the men that had been called into service as fast as possible. He went into the fight in which he was wounded without knowing anything about the cause of the war, or any knowledge of the state of affairs; he took it for granted that the Indians were to blame. When he came to treat the true state of things presented themselves piecemeal, and finally all the facts threw the blame on the whites. That he was much disgusted with their conduct is proven by the way he carried out the treaty, in spite of all opposition. The good people of the valley are much in favor of Lane's measures, but they are in the minority. The majority is made up of miners, gamblers and outlaws that have fled beyond the restraints of the law, and they cry against the treaty because they would lose nothing by its renewal, and they care nothing for the wives and children of the good settlers, who must be the sufferers in the main. These men do not hesitate to threaten to break the treaty whenever an opportunity may offer. Though they dare not openly resist the General's authority, yet he has been detained here, though all operations are at an end, because he fears that the moment his back is turned the war would begin again; he has been waiting the arrival of regular troops that the treaty may be enforced and these vagabonds held in check. According to the conditions of the treaty the Indians are to receive sixty thousand dollars, to be paid in sixteen annual payments, for their land in Rogue River Valley. Fifteen thousand of this, however, is to be retained to reimburse the settlers for the property destroyed. A small reserve has been set aside unto which they have retired, included between Rogue River and Evans Creek, and a line running north from Table Mountain to it, intersecting with Evans Creek. For this reserve they are to receive fifteen thousand dollars when the whites are fit to remove them. During the entire pending of the treaty the Indians have shown a patience and forbearance and a desire for peace that would hardly be expected from them, in consideration of their success and their independent character. The medium of communication was the jargon in common use in Oregon and Washington territories, and consequently explanation was slow and imperfect. All the Indians concerned in the war were present at the treaty, except the Taylor Indians and Tipsu Tyee's band. The former have only been warred upon in the manner related--they have not retaliated. The latter are Shasta Indians, and they were the ones who committed the first depredations. Gen. Lane, having finally concluded this treaty, set out in search of Tipsu Tyee. Confiding in the honesty and truth of these Indians, he set out with only an interpreter and a guide. High up in the mountains, on the head of Applegate Creek, he found them, near the summit of a lofty peak, beyond the reach of white men, living on the manzanita berry. They were in an impenetrable jungle, only thirty warriors in all, with their women. They had but fourteen guns. Tipsu Tyee is superior to any of the chiefs in this valley. He commands his men like a tactician, and they obey him implicitly, and without dissent. He reigns in these mountains like brigand chieftain. He is a small, heavy-set man, with little eyes, piercing and dark, and quite a growth of hair on his chin, from which he takes his name. The General found him disposed to peace. He said he himself had taken no part in the war, but that one of his tribe, a bad man, had persuaded a few of his men away, and they were the ones who committed the first outrages on the whites. As soon as he had learned the state of affairs he had gathered his people together and moved them into the mountains, where he had remained ever since. He promised to deliver up the leader of his party and such property as he had in his possession that had been captured from the whites. He lays no claim to Rogue River Valley and said he would return to Klamath River Valley, where he belongs. The present of a few clothes were offered him, which has concluded the last act of the treaty of peace, and it only requires that the whites adhere to it, and peace will be established and maintained. Col. Wright, with three companies of the Second Infantry, arrived here on the 25th. The evening before his arrival Jim came in and reported that a party of whites, passing down the river the day before, had fired upon his people fishing in the river, and also into their camps at different points--that the bullets had passed through the clothes of some of their people, but no one had been killed. The Indians had formed an ambuscade through which these white men had to pass, and that they would all have been killed, had not Joe got wind of the affair and, mounting a horse, reached the ambuscade before the whites and dispersed his men. On the 26th, Col. Wright, with Capt. Smith's company of First Dragoons, accompanied by Gen. Lane, made an appointment with Joe and his other chiefs and met them at the mouth of Evans Creek to talk the matter over. Col. Wright says that he was much impressed by Joe's bearing and dignity, and, like Gen. Lane, is fully impressed with his integrity. Joe said that he was fully convinced that the white men who had fired into his people were cultus tillicum--good-for-nothing people--and that he had for that reason prohibited the people from firing on them, because it would have been an excuse if they had killed them to renew the war, and he wanted peace. He seemed to comprehend the state of society in that region well. It appears that the outrage was committed by a party of Bob Williams' men, who had been discharged and were going back to Althouse Creek to work. Measures will be taken by the Indian agent to bring them to justice. This outrage decided Col. Wright to establish a fort here. He approved of the point selected by Capt. Smith, and called it Fort Lane, in honor of "distinguished services rendered by Gen. Lane in the recent disturbances." It is situated about three miles west of Table Rock, on a beautiful spot, with sufficient trees, oak and pine, for shade trees, and about half a mile from the river. Its plan will be about eighty yards square, with the buildings on three sides, and the side toward Table Rock and fronting the river open. The buildings will be temporary log cabins. The post is to be commanded by Capt. Smith, and garrisoned by three companies of the First Dragoons and one of the Second Infantry. The troops having arrived, and a prospect of the peace remaining unbroken, Gen. Lane took his departure for home. He expects to be in San Francisco on the 15th, in time for the steamers for the States. He takes with him to Washington one of Joe's sons, named Ben, an interesting boy of fifteen or sixteen. He will create a sensation equal to his own astonishment at the Bostons (Americans). U.S.

New

York Herald, November 14, 1853, page

3 Probably

authored by August V.

Kautz.

Reprinted in the Washington Sentinel on November 17, on page

2.OREGON CORRESPONDENCE.

PORT

ORFORD, O.T., January 1st, 1854.

Dear "Spirit"--You

will look in vain for Port Orford on the map. You may find Cape Blanco,

but that ain't Port Orford; though better navigators than either of us

have taken one for the other, we are eight miles farther

south. No doubt so small a distance is not estimated by you, seven thousand

miles distant, by the road [you] must travel, but still we like to know

where we are, and having settled that point we will proceed.Port Orford and Fort Orford are synonymous terms; the latter alludes to a few log cabins adjusted, like Peter Funk's hat, slightly on one side, and an old tarpaulin stretched over some poles for a stable, with one officer, a sergeant, and five men constituting the military establishment which is to protect and watch over the interests of a heterogeneous class that has built up the former--a mining village, with a dozen houses situated on a little bay opening to the south, from whence it receives the full benefit that may be derived from every southeaster that blows. Here the miners who grub among the sands of the seashore from the Coquille to the Rogue River get their grub; that is they used to do so, but don't now, for the place is nearly starved out. The San Diego left San Francisco freighted for this port near two months ago; and we since heard that she capsized and got into Puget Sound a perfect wreck, and the loss of nearly all our winter's supply of provisions. There has another schooner started for this point since, and she has not been heard of yet. We may never hear of her, but that is no reason that we should starve, and as the steamer won't land us any freight, we all expect to turn Nimrods and move into the mountains, which are not far off, and said to be thronged with elk, though it takes a Nimrod who knows how to hunt elk to get them. We are not many, but mighty, so the Indians think, who, though they outnumber us ten to one, give us no trouble, and treat a Boston with great respect; that is they won't steal his last shirt before his face, or back out from a bargain until they have ascertained with some certainty that they have the worst of it. Owing to the capacity of their stomachs for anything that is digestible, they are better provided with a winter's supply of provisions than the Bostons, for a zee-la (whale) was driven ashore a few days ago, intended no doubt as a providential interference against the approaching famine; but the Indians had cut it in pieces before the whites could approach it, so penetrating is the smell of anything fresh to the starving Bostons. It was a great windfall (of course it was the wind blew it ashore) for them; they have "hiyou mucka-muck" now (plenty to eat). Since then every morning a caravan of squaws, each loaded with a large quadrangular solid, a portion of the before-mentioned zee-la, enough for any mule, pass through the town up the hill by the garrison, all in single file, the largest in front, dwindling down to the smallest "klootchman" (squaw) behind, transporting it to their rancherias on Elk and Six rivers above. On it they will feast, and do nothing else until it is all gone. The Indian is a great epicure--of quantity, not quality; and a dish of whale oil is valued not for its purity, or cleanliness, but in proportion to the mass. Since my arrival here, the elements have had a great row, and not wishing to interfere with them in their trouble, I have been prevented from looking about me much to ascertain the nature of the country I am in. And the difficulty is not settled yet, for the winds howl, the skies threaten, and the sea is restless and uneasy. Not until peace and calm is restored will I venture among such an unruly sea. It is a source of regret that many [sic] can't have a meteorological reporter here, for he could get wind, and rain, and storm enough in one winter to satisfy a man with his excessive fondness for such things, and from that amount of data he could come to the conclusion immediately that sailors have no business to be at sea on this coast. It is well that he is not here to endanger his life by personal observations. For if he ventured out in some of the storms that we have here, he would himself become the straw that would show which way the wind blew; he would be whisked up like the foam upon the beach, and be carried off with these seeming clouds of feathers, and the gulls, to leeward. The rain does not come from above, but it comes along horizontally from somewhere in the horizon; it does not fall, for if during a lull in the storm for a moment a worn-out and exhausted drop should seek the ground, the next gust would pick it up and drive it along again, unless it hastily creeps into the sand. On the night of the 25th Nov., we had a terrible rumpus--all the witches of the air, the demons of the storm, and the genii of the earth were abroad, and like the wizards of old, they played sad havoc among the things of men and earth; such as taking down fences, and setting them round where they should not be, pulling up trees by the roots and laying them across the roads, pushing and pulling at the houses, making the inmates tremble with fear, removing piazzas and porches, and tearing long ragged ribbons from canvas houses, and playing in the wind with them; and one house was taken entirely to pieces. All of which would not have been so serious, if they had only returned them after the example of their old ancestors. But this they neglected to do, and the confusion of the inhabitants, the next morning, could only be compared with the things about them. Everything was topsy-turvy, the roads were blocked up, everybody's fences were on everybody else's gardens; a new bowling alley was taken possession of by the furies, who took the liberty of taking the first roll, and the first roll turned it over, knocking down several pigs as well as the pins, a "thirteen or fourteen strike in all," and the adjoining grog shop was left without an alley in more senses than one. The banks for fifty feet from the shore were white with foam, showing into what a rage the sea had been lashed by the excited furies. I was roused the next morning by my man McFalls, who, with a gloomy and sorrowful visage, recounted the devastations of the night. He held in his hand two odd socks, dripping wet and dirty; for two days he had been washing my clothes, and in consequence of the rain was compelled to hang them up in his temporary wash house, by the stove, and the panels of the door had been driven in by the storm during the night, and scattered his washing about in every direction, so that they had all to be washed over again. All this he recited with the deepest emotion such a string of mishaps could call forth, and holding out the two unfortunate socks, he concluded, "and shure sur, the're all odd, I can't find nerry mate, high nor low." Finally the demons of the storm hauled in their horns, the furies of the winds having "cracked their cheeks," as well as everything else, ceased to blow, and the sun having smiled on the havoc that had been created since he had last seen us, I thought I would venture on a little expedition up Rogue River, with the Indian Agent and the Doctor; you will observe that I am always accompanied with an Indian Agent and a Dr., two very necessary personages in an Indian country. The object of the expedition was to hold a wawa (talk) with the Shasta-Costa Indians, who had recently shown themselves a little hostile, when the Agent expected, relying on his persuasive and logical powers, to convince them of the absurdity of quarreling with their best friends. We set out on a day that promised fair but lied, for it was very foggy. We traveled down the coast for the mouth of Rogue River with the intention of taking canoes there, to ascend the river. Our road was one of the muddiest and roughest trails I have ever had the privilege of testing by doing half the walking on, notwithstanding that I had an excellent mule. We hoped to reach Elizabethtown in one day, but this hope was dissipated, by a couple of the animals concluding to camp at the end of twenty miles, so we stopped to keep them company. We camped near a village of the Euchres. The first night out in a trip like ours is always the most embarrassing, but with the exception that the fire would not light for a long time, and that it was sandy where we camped, that we had to take our supper after dark, that it rained in the night, and we were wet in the morning, and found the Indian dogs had stolen all our pork, we got along very well. But the rain continuing, and our fire being out, and wood scarce, and Elizabethtown only five miles distant, we rode on without our breakfast, which we took at a late hour after our arrival. Elizabethtown is a mining village, some four or five miles from the mouth of Rogue River, that has sprung up during the summer, built by the miners who are digging their "everlasting fortune" from the sands on the beach. As it continued to storm and rain all day, we did nothing but make arrangements for our canoes. However, had the wind and weather been ever so favorable, we could not have done any more, for it is a good day's work to deal with Indians for their canoes, with men to man them, if you have nothing but shirts and blankets to offer, for the men wear nothing, and the women cedar bark. We intended to start early the next morning, but we didn't, unless about noon may be so called; this arose from the fact that though we were ready, the Indians were not. It is a pleasant fiction when we insist that we ascended Rogue River in canoes, for though the canoes went up as well as we, we took the shore, and the canoes took the water. Occasionally, here and there, where the steep precipitous banks impeded our progress, they would set us across the river, and we were sure to find a bar on the other side, where the walking was quite convenient. In this manner we went about ten miles the first day, and at sundown encamped near an Indian village. Here we were the wonder of the evening, and quite a large crowd waited upon us, and though quite as much annoyed as Kossuth and suite in America, common politeness constrained us to receive them, though I have my doubts whether our consideration was appreciated, for they had the impoliteness to insist on sharing every mouthful we ate during supper. We had passed quite a large village during the day, and this was the second. The Doctor and I went up to witness one of their dances, but it proved a farce, as such things often do in more civilized countries. Two Indians kept time with sticks upon a board, whilst half a dozen others hopped about in a stooping position, much after the manner in which one would conceive a frog would dance, supposing that animal under musical influence. They failed to get up the necessary excitement, and proved very monotonous, and as we bid them goodbye with more politeness than was absolutely necessary, they themselves confessed that it was "wake kloshe," which, for the edification of your Irish readers, I will state means not good. The next morning we found the same difficulty about starting that we did before. The Indians, having waited very patiently for the leavings of our breakfast, found it necessary to increase that amount, to complete their meal for the morning, as we could not afford to feed Indian dogs and their masters too. Finally we were under way. As we ascended, the hills closed in more closely, and high and steep precipices overhung alternately each side of the river. One of our Indians, the war chief of the Tututnis, had gone ahead in the morning to kill a deer, but he changed his mind and killed a panther--the presence of the former having been interfered with by the sudden appearance of the latter. It had a magnificent skin, which the Indian Agent, by virtue of his office, contracted for immediately. We continued to foot our way along the shore and base of the rocky precipices, except where they overhung the waters at too great height, and then we declined climbing over them, but would let the canoes either cross us over or take us up a few hundred yards, where we would again find a footing. The Doctor was following close behind me, and behind him was my man, McFalls, a tall, raw, awkward Irishman, and everybody else still behind him a long distance, when we three were suddenly thrown into the worst stage of the buck fever by the sudden appearance of a young buck around a rocky point; he was in the middle of the river, and swimming diagonally down and across the stream. As I never was known to get my gun off when I most wished so to do, I did not deviate from my usual custom on this occasion, and capped and recapped without obtaining the climax that I desired. In the meantime, the Doctor fired, and as he had no faith in his gun, notwithstanding that it was a very good one, he missed, of course. McFalls had one of Hall's carbines, old and condemned, which, being overanxious to redeem itself from the disgrace into which it had fallen, went off before he had quite decided in which direction he was going to fire. At last, the deer having got a long way off, my gun went off a long way, too. Our Indians--that is, those in the canoe to which the Doctor and I belonged--having satisfied themselves that the shots did not proceed from an ambuscade, glided rapidly across the stream and reached the opposite shore a little before the deer, and one of them jumping out headed it into the water again, where they de-headed him in a few moments after, by knocking his brains out with a sharp paddle. Compliments to ourselves were unnecessary, but the remainder of the party behind could not refrain from flattering us a little in their peculiar way, congratulating us on having won the leather medal that is always supposed to be at stake on such extra occasions; we returned the compliments on our guns in curses, not loud but deep--too deep for utterance here. We had not proceeded much farther when we were startled by the howl of a wolf, on the hillside, and the dismal tones echoed from cliff to cliff with a mournful effect until we were out of sight; this was made an excuse for stopping and camping. They said it was bad luck to go any farther, and unless we turned back we should all be killed to feed the wolf who was howling for our dead bodies. This was a capital joke for us, and we laughed at the enormous appetite that wolf must have to want to eat us all up. With them, however, it was serious, and they insisted on camping and stopping for the night, though it was not three o'clock in the afternoon. The Doctor and I, and several of the Indians, went out to try our skill deer hunting. I climbed a long hill and came down again, and could only see where deer had been quite plenty too evidently. The Doctor saw five, but could not get his gun off in their presence, and after they were gone it was considered by him unnecessary. The Indians saw some also, and fired once, but not with the accuracy that was necessary to secure us some venison. One of the hams of the young buck made us an excellent supper. The old chief with whom we had contracted for the canoes was either superstitious or obstinate, or both, I don't know which; at any rate, he quarreled with the other Indians before we went to sleep, and the next morning, before we were aware of it, he got into his canoe by himself, and put out down the river. We feared that our further progress was stopped, but on inquiry we found that a canoe had come up the evening previous and camped with our Indians; a bargain was immediately entered into, and by the time it was concluded we were all ready to proceed, so we had quite an early start. With hard travel over rocky shores and high hills, on our part, and heavy poking and paddling on the part of the Indians, over the rapids, we reached the mouth of Illinois River, quite a large branch of Rogue River, about noon. This point proved to be the end of our journey, as we found quite a village of the Shasta-Costas opposite the mouth of this stream, where we encamped. Our Indians, in advancing upon this village, moved very cautiously, and with some apprehension. We had with us the "Salmon Tyee" of the Tututnis, who has charge of all the fisheries of his tribe. He is a curious specimen. He possesses what might be called strongly marked features, for his entire face was battered and scarred, but particularly about the mouth, which conveyed the impression that he had once possessed an enormous entrance to his masticating organs, and that an attempt had been made to darn it up to a more moderate size, for which purpose gashes seemed to have been cut all round it, to make the flesh yield more readily; and the prominence of his eyes, and the preponderance of the whites enhanced the impression that it had been drawn very tight. On this individual the Doctor had performed an operation, the success of which had raised him very much in the Indians' estimation. His mouth had been made too small, if the above was the process, for it would barely admit the little finger of his five-pronged fork, and he was consequently a regular and legitimate sucker, and passed by the name of old Screw-mouth. We passed this old fellow's hut the first day out, and as he volunteered to accompany us we took him with us. The Doctor had cut in on both sides of his mouth, giving his countenance more openness, and certainly improving his appearance very much. He was very grateful, and as we came by, presented the Doctor with a deerskin robe, and a handful of ten-cent pieces; the latter the Doctor wished to return, but the old man looked offended, though such an expression in his features would be difficult to describe. The robe the Doctor prized, and immediately called it an heirloom, though how it became such in so short a time I cannot conceive. We certainly found him a great help to us, and he was evidently the most reliable Indian of our party. He took the lead as we approached the Shasta-Costa country on the last day, and leaving the canoes three or four miles below the village, we took the trail over a high mountain, and the old man carefully inspected the trail, examined every stump and bush by the way, to guard against a surprise; the others were equally cautious, and much more alarmed, and I am confident that a single war-whoop would have left us without a guide or a canoe. The Shasta-Costas, however, were very friendly to us, and during the afternoon some thirty warriors collected, and the talk came off. They were all seated round, some of them hideously painted. The old chief came forth from his sweat-house, wrapped in his blanket, and seating himself with the Indian Agent on a slab, the two interpreters between them, the "wawa" commenced. The Agent's speech was first translated into the Chinook jargon, and then into the Indian tongue. He began as all Indian Agents' speeches do, with the greatness of the great Tyee at Washington, who had sent him, and the greatness of the Bostons, who were all his people; of his peaceful disposition to those Indians who did right, and how terrible he is to those who do wrong. After entering into an agreement for the punishment of all malefactors, the Agent concluded by saying that the great Tyee would reward them if they were peaceful, and would punish them if they broke the peace. The Chief was then asked what he had to say. The old man was rather [more] amused than embarrassed at the question, though he replied that he did not know what to say; another old man, however, who seemed "gifted with the gab," as they say out West, and moreover familiar with state affairs, and was probably the Chief's prime minister, came forward, and said that they were a peaceful people, that they minded their own business; that if the Bostons would do right they would do right, and that they would endeavor to conduct themselves so that when the big Tyee came to distribute the rewards they should also be entitled to their share of the presents, and wound up with a broad hint that they were always ready to receive presents, and hoped that when any such distributions came off that they would be informed of when and where they were to be made. These sentiments, delivered three times over, in a different form each time, made quite a speech, and the old fellow walked off, at its conclusion, as though he had accomplished the particular object for which he had been created, and would henceforth appear on the world's stage no more. It was near night when the "wawa" closed, so we decided to remain all night where we were. The Shasta-Costas said that they were at war with a tribe upon the river who had recently killed one of their warriors. As that was none of our business we thought they might fight away. Still, it disturbed us a little that night, for about midnight old Screwmouth, sitting in front of the tent where we slept, by the fire, raised the tent front, and as I was in front, his swarthy hands fell upon me, rousing me in a moment. The light of the fire was shining full upon his grim features, and his protruding eyes seemed entirely out of their sockets. Nodding up toward the woods, he said, in half-whisper half-whistle, through that wonderful mouth of his, "Shasta-Costa!'' I was about to "surrender at discretion," for I took it for granted that we were surrounded, and that the next thing would be a volley of bullets, or, what I feared still more, a shower of arrows through the tent, and consequently right through us. But the rest of the party being roused about the same time, they snatched their guns and resolved to die fighting; so I resolved to do the same, and seriously contemplated loading the empty barrel of my shotgun with duck-shot, and, notwithstanding that I had missed every bird that I had shot at since I left Port Orford, I thought that with my six-shooter and it I would kill seven or eight at least, and sprinkle the eighth well with fine shot. Unfortunately, however, for the display of our heroic and momentary dreams of desperate rencontre, we found it to be a false alarm, and were surprised to learn that the Shasta-Costas were our friends, but that the tribe above were not; that they expected an attack that night; that if we would assist them we could whip them, and that if they did not come down that night they would go with us the next day and whip them at their own homes. This did not suit the peculiar valor that influenced us, but (of course) we were much disappointed, and, though we went to bed again, we could sleep no more from pure aggravation. Our Indians became so friendly with the Shasta-Costas that they were loath to part the next morning, and it was quite late before we got under way. Once started, however, we progressed more rapidly than when coming up; it was no longer an uphill business; on the contrary, we were evidently going downhill. We occasionally took in a little water, going over the rapids, that only wetted us a little, but, being insoluble, we were not much disturbed, chemically or otherwise. We passed over in one hour what required half the day before. We were only about five hours coming down; but our stoppages by the way made it four o'clock before we reached the Tututni village from which we had started. There was an abundance of ducks of various kinds on the river, and all our efforts to kill any going up only stimulated us to greater exertions coming down, but in vain. I blazed away at every favorable opportunity, upon the wing and upon the water, at every duck that came within range of what I had the conceit to consider a very good gun, (one of Mullin's [John Mullan's?]) and, though I may have hit one of them, they all flew off as if I had not, so it was all the same. Finally I had exhausted a two-and-a-half-pound shot bag and a large powder flask, all except the last charge, which I thought I would keep for a peculiarly favorable opportunity. A defiant duck at length allowed us to approach within thirty yards, and I blazed away again; and he floundered apparently with great agony in the water. I thought I had him, and dropping my gun, I seized a paddle and pulled away after him. In the haste and excitement of the moment--for the rapid current was carrying us by--I kicked the shotgun overboard, a fact I was not cognizant of until a splashing in the water behind me attracted my attention, and looking round, I discovered the Dr., with his head and shoulders under water, diving for it. To cap the climax, the duck, having satisfied himself that we were after him and nothing else, "took unto himself wings and flew away." Here was a handsome thing to talk about when we should get back, particularly as we went away boasting of the number of deer and elk we were going to kill, to say nothing of the small game; and here we had been out nearly a week, and "nerry one" did we kill. The Indian agent and Abbott, his interpreter, after a great deal of firing, killed a duck each, and the doctor, after shooting twice, killed a vulture [more likely a condor] that Abbott had wounded; he hit him the second shot--when he was so close that he could not possibly have missed him; he was very large--at least ten feet from the tip of one wing to the other. It is a mystery to me that we did not kill something more, if only by accident; for game was evidently plenty; we saw abundant traces of bear, deer, elk, beaver, &c., &c. We decided that mum should be the word, but that was impossible; so I have written it all down for the benefit of those who choose to laugh at us. A rain came on before we left the canoes and interfered with the awful punishment that we contemplated for the old chief who had run away from us with this canoe; we were going to shoot him, in the excitement of the moment, at first, only we knew that the Indian Agent would interfere; then we were going to flog him, cut his hair off, &c., &c. When we landed, however, it was raining hard and near night, and we had still three miles to walk. We stopped, however, and the Agent went through the ceremony of breaking the old fellow of his office as the Big Tyee of his tribe, and constituted the young war chief, who had been faithful to us, as the principal chief of his people for the future. It hurt the old man so much that he had the impudence to reply that he did not care whether the whites called him Tyee or not, his people would, for he had always been Tyee; he was the richest man in his tribe, and he didn't care for the whites, for they never did anything for him. And this was our revenge. I could not get an early start the next morning, but still I decided on going through, though the others stayed back; and though it was after night when I got in, thanks to my mule, whose superior knowledge put me right again, once, when I was lost in the woods, and when it was so dark that I couldn't see anything. I think I have written enough this time. I have no doubt you think that I "write but little, but I write that little long." I intended to write you about my trip through from Columbia River to San Francisco, but circumstances prevented, and it would be an old story now. That I intended to write, I will prove, by sending you the enclosed specimen of advertising, which I picked up in Umpqua Valley. The wind had no doubt torn it from some post or tree and borne it to me, and thence to fame--that is, if you will print it. HANS.

----

August the 25 umpquall Valy A Stray are Stoling mar went from My house

Last nite She has a yong hos Colt she is parte merican an is a litl bay

an blaze fase an white hind legs an is branded on the left hip with t S

an on the left Sholder C if any man sees her an sendz me word ore let

me no it i will satsfy himMr

Jessee Fouts

Spirit of the Times, New

York, February 25, 1854, pages

15-16 The author is apparently Lt.

August V. Kautz;

the Sub-Indian Agent F.

M. Smith;

the interpreter George

H. Abbott.HUNTING IN OREGON.

PORT

ORFORD, O.T.,

Jan. 9, 1855.

Dear "Spirit"--If

I have not written to you for so long a

time, it has not been because I did not think of so doing; on the

contrary, I

have often thought of it, but have been Micawberizing

or

Micawberating (which would you call it?) but nothing will turn

up. I give

you my note of hand at last, renewable at any time, and

particularly when

anything should turn up.I have been on one or two elk hunts, that were in themselves very interesting hunts; not that we killed anything, for I was never known to do so tame a thing, and I generally have sufficient address to prevent any of my fellow hunters from committing the like. I have no apprehensions from the game laws, nor need the game laws have any apprehensions from me. We generally talked of killing something, but that was only to give our expedition the character of a hunt. The most delightful excursion was with the Judge, the Doctor, his son Charley, and Kossuth; Kossuth, you know, is a Hungarian. [Lajos Kossuth didn't visit the West Coast.] When we set out, the Doctor said he knew where we were going, and when we got upon Strong Point he boldly turned to the left, and one would have supposed that he really did know where we were going, notwithstanding that the trail we were following was quite invisible, and led us directly into the forest-covered hills, leaving the sea behind us. This was scene first, and was enacted about one o'clock, P.M. Scene second transpired about four P.M., at precisely the same spot, with the same characters, somewhat altered in appearance, it is true, but evidently the same. They were coming out of the woods, instead of going in, this time. I was leading John, the one-eyed pack mule, and we two led the party. John and I had evidently turned back, because John and I, with my two eyes, and his one, could not see how we were to get through, particularly John, who had on his back about a dozen loaves of bread, a ham, and camp utensils, enveloped in the entire bedding for the whole party. It was, therefore, rather difficult for him to get through an undergrowth through which nothing but a coyote or raccoon had ever passed. Next came the Judge, his appearance somewhat altered; the perspiration had considerably disturbed the rigidity of his immaculate collar, a circumstance that probably had not occurred for years before, whilst the precision of his other clothing had also been infringed upon; his struggles had evidently been severe in the "recent brush," and as he set his gun down against a tree, he looked as though if he were "monarch of all he surveyed," he would have given it all that moment for a drink of water. Kossuth and Charley came next; they were evidently supernumeraries in the scene, for they stood in the background, and were evidently laughing at their own performance. There was much dilapidation in their personal appearance; branches had evidently come in contact with a tender limb of the law, and the hero of a revolution had been himself revolutionized. The Doctor came last--that was because he went in first. He looked serious, and had evidently come to the conclusion that he did not know where he wanted to go. A consultation resulted in the conclusion that it would require more game than we possessed to reach where game could be found that night. So scene third found us about ten miles from Port Orford, encamped for the night; and as our eyes closed in sleep, so did the first act of the comedy we were playing. The next act carries us through several scenes, in which Charley goes hunting for the animals the next morning, and sees some deer, which he would have shot if he had had his gun with him, fortunately for the deer; and we pack up and move off toward Bald Mountain. About eleven o'clock we reach our camp, and Kossuth, with his accustomed disinterestedness, volunteers to remain in camp to protect the aforementioned loaves of bread and ham; the rest of us all start out in different directions. As usual, when hunting, I lost sight of the game I was after, and which this time, by the way, I had not seen yet, and climbed the neighboring hills to the summit of Bald Mountain to get a view of Port Orford. I saw it fifteen miles distant; but, having seen it, my next thought was to get back to camp, for night was coming on, and I was at least five miles off. Of course, I had little leisure to hunt, and night overtook me a mile from the camp. The closing scene of that day's hunt is a tall, dark forest, a thick undergrowth, and I in the midst of it making my way back to camp according to general principles of locality, when I suddenly disappear from the stage, not through a trap door, but an elk trap, about eight feet deep. (Elk traps, in this neighborhood are pitfalls dug by the Indians for catching elk and are usually eight and ten feet deep. They are very plenty in the forests, but are no longer used now.) When I get to the bottom my feet are up, and my head down. Two friendly poles enable me to get upon the stage again, with the loss of my ammunition, which I do not discover until I am out, but having been deprived of all interest in such deep matters, do not feel like making a useless search on so dark a night. I am barely able to comprehend the large horn growing out of my head, with my sprained hand; I feel it, and it seems much larger than it really is, perhaps. I finally reach camp, where I am laughed at, though why they laugh at me I cannot conceive, for none of them have killed anything except the Judge, who shot a grouse, half of which he has kindly saved for me. The Doctor saw a bear, why didn't he shoot it? It was not close enough, I suppose, or perhaps he could not get close enough; some people find it very difficult; I don't think I could get close enough to a tiger. No one else has seen anything, and as we are tired enough to sleep, the curtain drops. It rises again the next morning very early, and the first scene opens with several hunters going out to kill a deer or an elk before breakfast. Scene second finds them all back again, discussing, in addition to their cold ham and coffee, the propriety of returning home, and it ends in packing up. The last scene of that day is the finale of the drama, and exceedingly well played. We again reach Stony Point, and are wending our way round it on the rocky beach, instead of over it. The Doctor is leading off, next comes the Judge. No. 1 is No. 3 this time, and Kossuth, with the one-eyed pack mule in advance of him, is bringing up the rear. John's load, although relieved of most of his bread, has rather gained than lost in weight, for a thought of our friends induced us to purchase a ham of venison of some half-breeds, who had fewer scruples or more skill than we. Our friends were evidently contemplating a rich meal from our chase, and we did not wish to disappoint them altogether. Charley had deserted us, for though he had killed no more than we, he thought it would be disreputable to be seen returning with such a party, and left us for Rogue River. In the above order we were nearing the Point, when a fine buck with a noble pair of horns (seen by the Doctor, but no one else), comes quietly down the ravine, a few yards ahead of us, and walks into the surf for a bath. In the meantime the Doctor has dismounted and re-caps his rifle, an operation that attracts the curiosity of the Judge, who is thereby led to the discovery of the deer, and with an addition of a little haste to his accustomed deliberation, he also dismounts to reprime his rifle. "Gods! look at that deer," says he. I don't suppose that the presence of the deer inspired him with a divine reverence for me, but the remark is evidently intended for me, so I look and dismount in great hurry also. The Doctor fires, and as the deer comes to the conclusion he had better get out of this, he turns for shore, and it is presumed that the Doctor has missed. I am afraid someone will kill him before me, and as my gun needs no priming, I run forward and fire away, and miss also, of course. The Judge finds that his gun will not go off, notwithstanding that he has recapped it. In the meantime the Doctor forgets that he has a five-shooter in his belt, and makes an effort to catch the deer by the horns, and does not remember his pistol until the buck is fifty feet up the bank, which is very steep, in consideration of which the animal stops and looks back to see the Doctor fire at him. As the Doctor does not bring the deer down with his five-shooter, I try my Navy size, and fire five times, but the very shot that probably would have killed him did not go off. The Judge, having recapped his rifle three times in vain, thinks of his revolver, and fires three rounds before he gets beyond shooting distance. The part that Kossuth plays in this spirited scene is that of an excited spectator. The one-eyed pack mule is just in advance of him, the path narrow and rocky, and he cannot pass. Moreover I had persuaded him to discharge his rifle at a pelican in the water, without any prospect of hitting it, and had not thought it necessary to reload so near home. Seeing the deer pause to be fired at, he hastens to reload with a precipitancy that pays no regard to what he is about, and before the deer is three hundred yards distant he fires, and by the time the deer goes two hundred yards more he fires again, making the seventeenth shot that has saluted this humble inhabitant of the forest, for which attention he does not bear us the slightest mark of esteem. I have a great curiosity to see where he goes to, and follow over the Point to ascertain, a distance of two miles up a very steep hill and down again. In the meantime Kossuth, with his accustomed kindness, takes charge of my mule for me, a task that he finds somewhat embarrassing, as the mule will neither lead nor drive. After all his persuasion he finally dismounts and leaves his own mule standing, in charge of his gun, which he leans up against his foreshoulder, a responsibility that the mule shrinks from, and the gun, left to its own resources, "falls as though it had been shot." At this juncture I reappear, and save Kossuth a violent passion, and the mule a severe beating. I came to the conclusion that any lengthened pursuit of such a deer would only be a wild-goose chase. It is unnecessary to relate how our friends received us, particularly when all the particulars were detailed to them. Kossuth and I, not satisfied with the result of this expedition, went out again a few days after, on which occasion we got belated returning to camp, and became entangled in an undergrowth that was more impenetrable than the darkness--a very alarming position to one with my experience in elk traps, which we avoided only by following down a stream in many places waist deep in water; where it exceeded our boot tops Kossuth mounted on my back, so that we might preserve at least one pair of dry feet in the party. The next morning our mules had become dissatisfied with the expedition and returned to town. On my proposition that one of us should go for the mules, and the other remain to hunt, he chose the former with his usual disinterestedness. He would always sacrifice himself, though I had my suspicions, in this instance, that salvation was the motive, and that he had misgivings of not being able to return to camp, and he chose to hunt mules, who follow the track, to elk who do not. I was fortunate enough to kill a grouse; by dint of a good support, and firing twice, I succeeded in taking its head off. Afterwards I saw an enormous elk, but it must have been an optical delusion, for I fired right at its head, within the distance of a hundred yards, and never touched it, though it was considerably moved, evidently. When I got back to camp, Kossuth had returned with the mules. When I told the story about the elk, and produced my grouse, he found it very difficult to comprehend how I could shoot off the head of a grouse, and then miss an elk, and I confess it is somewhat difficult to comprehend. He insisted that I must have lassoed it. We returned with our own views of elk hunting somewhat altered, since which time we have hunted elk no more. We eat a great deal of elk, but we obtain it as we did the ham of venison. We fish sometimes in the bay, and catch plenty of rock fish. The salmon fishery is quite successful at Rogue River. They catch them with a seine, in great quantities. They have caught four hundred at a single drag, varying from fifteen to seventy-five pounds in weight, each. I believe I will close with this fish story. I hope it will lose no interest by being true. HANS.

The Spirit of the Times, New

York,

February 17, 1855, page

2Fort Orford O.T.

My Dear Cousin:May 11th 1855 It no doubt would be [a] waste of time in me to attempt to expose that woman's tact, which you possess, it seems, in as great perfection as anyone of your sex, with which you seek to put all the blame on my shoulders because you have not heard from me in so long a time, for you would no doubt with that same tact that I should seek to expose, turn the tables on one from an opposite direction. I will therefore only try to remind you that when you wish to hear from your cousin you have [to] but answer his letters, as he never allows a letter to go unanswered when one is required, and a letter put in the post office with Lieut. A. V. Kautz, 4th Infantry on it, even if you don't know my station, will find me out finally. I assume always that if my letter is not worth answering it is not worth writing, and my unanswered letters are therefore a source of regret to me, because I should have art [sic] so much time in penning them. Your letter seems to make up in warmth and promises what past indifference and neglect you may have been guilty of, and after so long a silence it comes with the greater force, reminding me how kind you might have been, but would not. Your promises seem earnest, and it will afford me much pleasure if you adhere to them and prove a faithful correspondent hereafter. I was in San Francisco when I received your letter. I paid that city a visit of three weeks, which was quite a holiday for me who had been shut up here in this place for eighteen months. I enjoyed myself very much, though I must say I suffered much going and coming from seasickness. I was very sick, and did not get over it for several days after I got to San Francisco & although I have been back five days now, I feel the influence of the ship yet and am quite sick sometimes. You may be sure that I stared when I saw San Francisco or "Frisco" as we call it for short, for it had improved so since I saw it last, and the wonders of the place entertained me all the time I was there. I have seen many cities much larger, but in its peculiar features none like San Francisco. You should see it, to know what it is, for I cannot describe its peculiarities. Its inhabitants are from every clime and you see creatures on the sidewalks sometimes and wonder if they are human beings. The recklessness of everyone, money is spent like kings disburse it, and the ladies dress like princesses. It contains more theaters, churches, gambling saloons and houses of public resort than any city of its size in the world. It is just a fast city, almost too fast, as the crashing of the banks too truly indicates, but nobody seems to be interrupted in their mad career and everything goes on full tilt as before. You may be sure that I came away poorer than I went, at least so far as money is concerned, and I am very moderate, for you know I have not been brought up in an extravagant school. I was therefore rather [more] pleased than otherwise to get back to the quiet and obscurity of Fort Orford and shall probably have the good sense to remain content where I am until the powers that be see fit to send me elsewhere. I have laid in a supply of books, music, colors &c. which will serve to pass the time even if I do not learn anything. The coming summer however I expect to spend in the mountains making a reconnaissance of the country, which duty I shall like very much, as I am fond of field service occasionally, particularly after having rested here so long as I have. I saw Genl. Wool when I was down, to whom I reported the state and condition of my post, and he was so well pleased with my services that he does not contemplate removing me, notwithstanding that the officers of my regiment have been making very strenuous efforts to have me returned to my proper command, which is at present at Fort Vancouver. But the General objects, so I see no prospects of getting away from this post whilst I remain in the country. I do not object, for when I know how long I am to remain in a place, I know what to do to make myself comfortable. At present I am leading a quiet and domestic life. I have comparatively little duty to do; the Indians give me no trouble, and the whites have learned to behave themselves. I have twenty-four men whom I manage to keep in pretty good order. I have pigs, goats & chickens & a nice garden so that my table if not elegantly supplied is at least abundantly provided for. I have a pleasant companion in the post surgeon, and being the only officers at the post of course [we] are obliged to be very sociable. We have no society whatever. There is one young lady in the place, but she is said to be engaged, and of course it would be cruelty to captivate her, or folly for us to fall in love under such circumstances. It is true we have plenty of Indians who undoubtedly belong to the first families of Oregon, but speaking a different language and possessing different customs and manners as they do we find it rather difficult to assimilate ourselves to their society, particularly in the matter of dress, for though a simple blanket forms a very picturesque costume, still it requires some experience to adjust it properly, besides among them the ladies do all the work and it shocks our idea of gallantry to have them carrying immense baskets of fish or potatoes whilst we walked with them carrying nothing. I must close. Remember your promise to write, and give my love to your father and mother and write soon too. Your cousin August. Beinecke Library Port

Orford

I share

quarters with Dr. [John] Milhau, a surgeon in the army, and who is my

only associate. There is but one young lady in the post, who is quite

pretty and intelligent. It is a pleasure for us to go and see her

occasionally and to take her riding when the weather permits. The

wonder is that we don't fall in love. The Dr. says I am and I say he

is, but everyone else says she is going to marry Mr. Dart, who keeps a

store in the place. We do not often go hunting, for game is scarce, but

plenty of fish are to be caught in the bay. The Dr. and I mess together

and have a soldier to cook for us. In Jan. our rum bill was $42, but

everything is very dear, prices very different from those in the East,

beef 25 cts. lb., butter 75 cts., eggs 1.50, potatoes 4 cts.When the steamer stops on the way up, we have time to answer our letters by the time she stops on her return, but very often when it is stormy she doesn't put in and then we must wait until her next trip. June

1855

I saw Gen. Wool and reported to him the condition of post. He seems so

well pleased with my services that there is no prospect of my being

relieved for a long time.