|

|

C. B. Watson, April 5, 1916 Medford Mail Tribune

A WONDERFUL HISTORY

Many of the readers of The Tidings have followed C. B. Watson's Reminiscences

throughout the period they have been publishing in this newspaper, and

the unanimous opinion of those pioneers who were fortunate enough to

have lived in the exciting and constructive periods about which Mr.

Watson has written is that his Reminiscences are accurate and a vivid

story of the early days in Southern Oregon.

Mr. Watson has now undertaken the most comprehensive and instructive writing he has ever given the public. This starts today in The Tidings and will accurately reproduce in words the history of this section in the pioneer days when, as one pioneer stated, "things surely did happen fast sometimes." This history will comprise one of the most valuable reference books of Southern Oregon history and will mean that many incidents which might otherwise be forgotten will be preserved and form an inspiration for future generations. The early upbuilding of a community is really the most difficult, just as the early period of development in a business is usually the most trying. Read this history and you will realize the true worth of those who cleared and assisted in making this region the paradise which it is today. Ashland Daily Tidings, September 22, 1924, page 2

Pioneering in Southern Oregon

By C. B. Watson CHAPTER ONE Troubles

with the Indians of Southern Oregon in times prior to any effort at

settlement there.--Jedediah Smith in 1828.--Kelly and Ewing Young in

1834.--The Turner party attacked at Foots Creek in 1835.--Ewing Young

and party attacked at Foots Creek in 1837.--Fremont attacked at Klamath

Lake in 1846.

Many books have been written about the early settlement of Oregon, all of which have merit, but none of which in my judgment are entitled without qualifications to be called a History of Oregon. An immense area of country lying south of the Calapooia Mountains has an entirely different history from that covered by the Willamette Valley and a narrow strip along the south side of the Columbia. The early history as chronicled by nearly all of the writers is confined to the operations of trappers and hunters connected with some of the many adventurous organizations organized for that purpose of Christianizing Indians. Until 1846 all entry into Oregon was overland to the headwaters of the tributaries of the Columbia, thence along that stream to the Willamette Valley where the missions were established, or by water to the mouth of the Columbia, thence up that stream to the universal destination as indicated by the various missions. The old missionaries are entitled to all the glory with which they have been crowned. From their efforts a wonderful civilization has been built up. In the very nature of things there arose various institutions of learning, some of which have ripened into colleges and universities, and the Willamette has become the alma mater of a great state. It is not my purpose to rewrite the early history of that section, nor to rehearse the adventures and hardships of the earlier pioneers into that section. For those who have not read it and desire to do so reference is made to the many books to be found in our public libraries and on the bookshelves of nearly every home. The very early settlers in the Columbia Basin early learned that there was an Indian trail running southerly over the mountains into California, and some of the Hudson Bay trappers had traversed it. The pioneers who had encountered the hardships of the overland journey from the Missouri River were only too glad to rest in the beautiful valley of the Willamette and had no desire for exploitation of other uninhabited regions. It is true that history recounts the adventures of Jedediah S. Smith, who in an effort to further his trapping enterprise endured heartbreaking adventure in trying to reach San Diego in Southern California in 1826, and from thence traveled up the coast into Oregon in 1828. He reached the mouth of the Umpqua River, where all but himself and three of his men were killed by the Indians, and his horses and furs and supplies were taken. After untold hardships they reached Fort Vancouver, where they were succored by Dr. McLoughlin, factor of the Hudson Bay Company. The employees of this company were known by the Indians everywhere in the Northwest, and the name of Dr. McLoughlin was held in reverence by them. He undertook to recover the property of Smith and to chastise the Indians for this act of barbarism. He accomplished this and returned the property recovered. This seems to be the first act showing the ferocity of Southern Oregon Indians. About the year 1834 the Rev. H. K. Hines reports a trip made by him to the Umpqua River in search of a suitable place to establish a mission. He found a trader in the employ of the Hudson Bay Company established on that stream opposite the mouth of what we now know as Elk Creek. He was warned that the Indians were unreliable and not to be trusted. He spent a few days there and in the neighborhood and returned to the Willamette missions without establishing a post and reported the Indians to be the most unmitigated rascals he had seen in Oregon. This is the first reliable word I have found at that date of the appearance of any early settlers appearing south of the Calapooia Mountains. Ashland Daily Tidings, September 22, 1924, page 2

It appears that about this time the Hudson's Bay Company extended a more active exploitation of this Southern Oregon country and operated as far south as the waters of the Sacramento River. In passing back and forth the Indians came to know more about white men and to learn something of the difference between the great company and independent trappers that occasionally appeared. It is said that in June, 1825, a party of white men on a trapping excursion entered Rogue River Valley and were attacked at the mouth of Foots Creek. There were eight of them including a squaw, the wife of one of the trappers. Four of these men were killed and the remainder badly wounded. In the transactions of the Oregon Pioneers in 1882, as narrated by J. W. Nesmith, the circumstances were as follows:  James Nesmith "Two years later, or in 1837, a party of Oregonians proceeded to California to buy cattle to drive to the Willamette. They secured a drove and returning, passed through Rogue River and Umpqua valleys. The party was composed in part of Ewing Young, the leader; P. L. Edwards, who kept a diary of the trip; Hawchurst, Carmichael, Bailey, Erequette, DesPau, B. Williams, Tibbetts, Gay, Wood, Camp, and about eight others, all frontiersmen of experience. While encamped at the Klamath, on the fourteenth of September, 1837, Gay and Bailey shot an Indian who had come peaceably into camp. This act was in revenge for the affair at Foots Creek, but that locality had not by any means been reached, and the Indians' crime of 1835 was revenged on an individual who, perhaps, had not heard of the event. The act was deeply resented by the Indians throughout the whole section, and the party met with the greatest difficulty in continuing their course. On the seventeenth of the same month they encamped at Foots Creek, and on the next morning sustained a serious attack of the savages, narrated thus in the diary of Edwards: "'September 18.--Moved about sunrise. Indians were soon observed running along the mountain on our right. There could be no doubt but that they were intending to attack us at some difficult pass. Our braves occasionally fired on them when there was a mere possibility of doing any execution. About twelve o'clock, while we were in a stony and brushy pass between the river (Rogue River) on our right, and a mountain covered with wood on our left, firing and yelling in front announced an attack. Mr. Young, apprehensive of an attack at this pass, had gone in advance to examine the brush and ravine, and returned without seeing Indians. In making further search he found them posted on each side of the road. After firing of four guns, the forward cattle having halted, and myself having arrived with the rear, I started forward, but orders met me from Mr. Young that no one should leave the cattle, he feeling able, with the two or three men already with him, to rout the Indians. In the struggle Gay was wounded in the back by an arrow. Two arrows were shot into the riding horse of Mr. Young, while he was snapping his gun at an Indian not more than ten yards off. To save his horse, he had dismounted and beat him on the head, but he refused to go off, and received two arrows, probably shot at his master. Having another brushy place to pass, four or five of us went in advance, but were not molested. Camped at the spot where Turner and party were attacked two years ago. Soon after the men on day guard said they had seen three Indians in a small grove about three hundred yards from camp. About half of the party went, surrounded the grove, some of them fired into it, others passed through it, but could find no Indians. At night all the horses nearly famished as they were tied up. Night set in dark, cloudy and threatening rain, so that the guard could hardly have seen an Indian ten paces off, until the moon rose, about ten o'clock. I was on watch the first half of the night.'" Here Mr. Edwards' diary breaks off, but from such information as could be obtained, the party had a very serious time in passing this hotbed of savages. So it will be seen that, many years before any attempted settlement of Rogue River Valley, the whites knew of the warlike character of these Indians. When we cross the Cascade Mountains among the Klamaths and Modocs we find the same spirit exhibited toward the Hudson Bay Company. The Indians seemed to realize that people who were coming in to make homes and to engage in agriculture; who were appropriating the soil were preparing to become fixtures. They were not furnishing to the Indian a market for their game and furs, nor living the easy social life of savages as many of the trappers did. They resented the attitude of superiority and were warned by the history of the tribes that had been subjected by white people in far distant regions and were not wholly ignorant of that history that found its way to them in many devious ways. In 1846 J. C. Fremont, pursuing his search for the "Great Klamath Lakes," which he had failed to find in 1843, traveled north through California, toiled laboriously up the Sacramento, reached Pit River, which he crossed, following its tributary, the McCloud, northeasterly to its source in springs and noted the great snow-capped peak to his left, knew that he was outside of any beaten path, but did not know the name of the towering peak that persisted in view for many, many weary days. Mount Shasta seemed to look down on him with compassion. He turned to the left where he saw a notch in the mountains that promised him an entry in the direction of his search. In this pass he noted lava beds of forbidding aspect and the rugged volcanic character of the country, but did not know that these fastnesses were the abiding place of the most ferocious savages in all the land. He was passing the lava beds where twenty-seven years later the Modoc War was fought and where treachery lured General Canby and Commissioner Thomas to their deaths. He rounded Tule Lake and called it Rhett Lake. From there he saw that the country opened into plains of sage and bunchgrass and that the mountains receded as he pursued his course toward the Northwest, believing that in his great basin he would at last see the Klamath lakes that he had searched for [for] so long. He finally reached the foot of "Big Klamath" Lake, and on its banks an Indian village. This spot is now within the corporate limits of the city of Klamath Falls. The Indians were not friendly but with the offer of valuable presents they assisted him to cross the lake and directed him to a trail that ran northerly along its western shore. He traveled a few miles and camped. From his higher ground he could see large numbers of canoes filled with warriors following along parallel with his course. He suspected hostile intent but with Kit Carson as guide and advisor he finally reached the north end of the lake, where he made camp on the 20th day of May 1846. On that evening he was surprised to see two men whom he had, at their request, discharged at Sutter's Fort in California many weeks before. These men were riding horses much jaded and lathering with sweat. They hurriedly told him that they had come with some army officers who were hurrying to him with urgent dispatches and orders from the War Department; that these men were many miles behind them and had hurried them on to overtake his command and urge that he send a detail to meet them. Their horses were badly jaded, and they thought that the Indians intended to attack them. Ashland Daily Tidings, September 26, 1924, page 2

Fremont and Carson with fifteen men at once left their camp and rode rapidly down the lake to meet these messengers. About sundown they met them and made camp. Lieutenant Gillespie delivered his messages, and Fremont, knowing all his men were very much fatigued, told them to go to bed without a guard, as he would have to be up reading his messages and mail until late and that he would call a guard before he retired. He finished his messages after midnight, and everything appearing quiet, he stretched himself by the fire without calling a guard. Just as he was dozing to sleep the Indians attacked. A lively fight ensued and the Indians were repulsed, but not until they had killed two of his men; one an Iroquois and the other a Delaware Indian. They had taken toll from the treacherous Indians and among others had killed a chief. Their departure from this tragic camp was a sad one. They attempted to carry the dead bodies with them, but the forest was heavy and the brush thick, which made it impossible without too great a delay. So they buried their comrades under a big log and piled logs and brush about them, having no tools to dig a grave. He had quite a number of Iroquois and Delaware Indians in his company, and when they had heard the story of how their comrades had been killed they swore vengeance against the savages who had murdered their brethren. Fremont was notified in the dispatches that the Mexican War was on. This was the first notice to him. He had been away for many months and had had no information. He was ordered to return at once to California and protect U.S. citizens and their property. He had traversed the west side of Klamath Lake on his journey to its head and now concluded to pass round the upper end of the lake and return along the eastern shore. Walling says in his history that the tragedy just narrated was on Hot Creek in Siskiyou County, California. This is a mistake. Hot Creek is at the south of the lower Klamath Lake and is entirely out of the line of Fremont's journey north, and the messenger and his companions had followed Fremont's trail all of the way. The place of this tragedy is well known by Capt. O. C. Applegate and others. Such a trip would have involved crossing the Klamath River and would have been noted in his memoirs if such had been the case. Besides, Fremont in his memoirs expressly describes the crossing of the lake at the head of Link River, which is the beginning of the Klamath. Walling is again wrong in saying that Fremont "traveled by way of Goose, Clear and Tule lakes to the southwest shore, where he camped for a few days." He was not nearer to Goose Lake than fifty miles and was, when rounding Tule Lake, at least ten miles west of Clear Lake. The writer is familiar with all that country and has read and checked up on Fremont's official memoirs. Ashland Daily Tidings, September 29, 1924, page 2

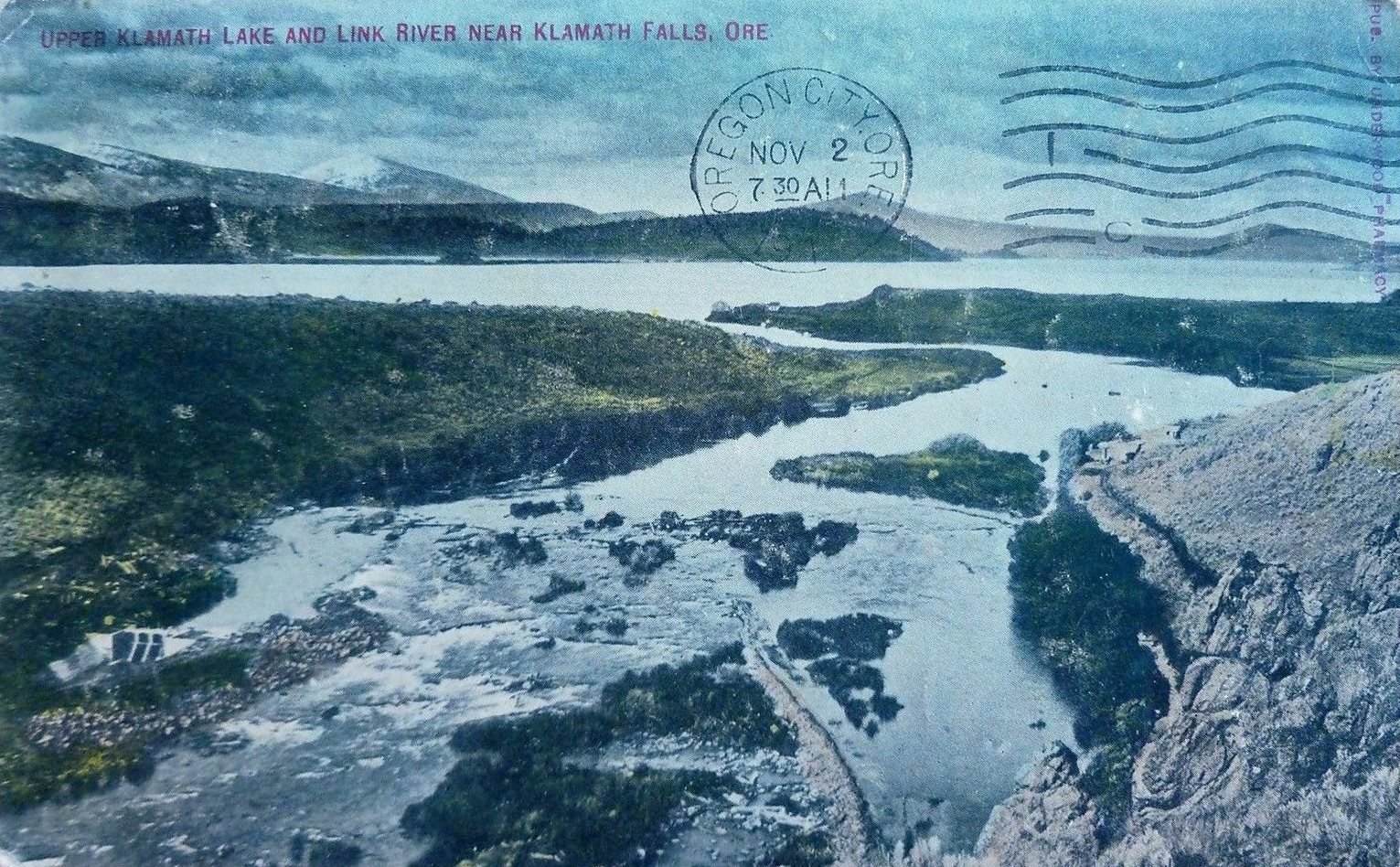

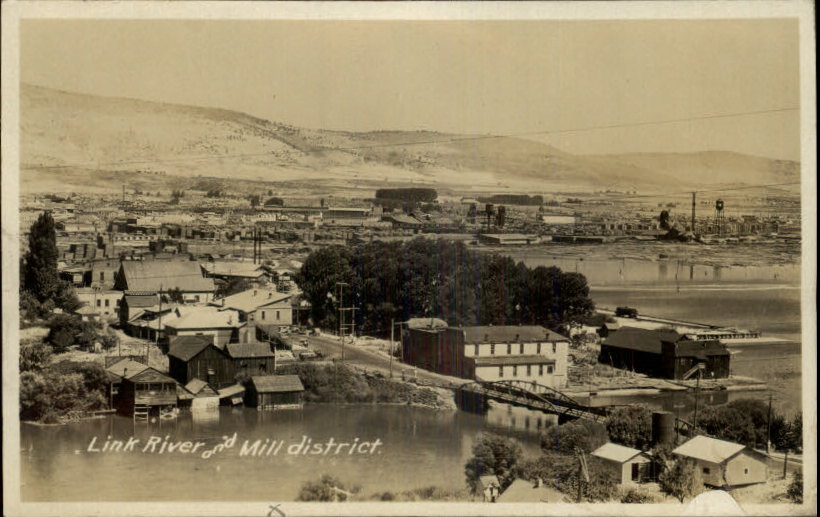

Link River. Postmarked November 1910  Link River, circa 1915. Fremont and Carson then hurriedly pursued their journey into California, there to perform their part in protecting citizens and adding the great state of California as another star in Uncle Sam's diadem. So we see what appears to have been an inborn hatred by these savages against the whites. In this same year, 1846, the Applegate party made its historic journey through Southern Oregon on an errand of mercy in the interest of pioneers still coming. This I will give in my next chapter. CHAPTER TWO

We

have chronicled the earliest entries of white men into the Southern

Oregon country dating from Jedediah S. Smith in 1828, followed by

others up to Fremont's exploration of the Klamath Lake country in 1846.

From these we have seen that the attitude of the Indians has from the

beginning been antagonistic.

From the establishment of the Hudson Bay Company a policy was adopted by them toward the Indians [which], while it was firm and dominant, resulted in amity between them. The factors of that great organization early realized that to gain their confidence they must, to a certain extent, assimilate with the tribes among whom they mingled. This could be best accomplished by having the trappers take native wives and to a great extent adopt their customs and live among them. The trappers were of that class not averse to the establishment of such relations, and the result [was] a general acceptance of the head factor as the dominant power, recognized by the natives through the trappers, who themselves came to be recognized as the representatives of this powerful organization. They were treated with consideration and their wants and rights were respected, but [they were] gradually trained to the purposes of the company, to which they looked for a market for their furs and such other articles as they might produce that found a place among the needs or conveniences of commercial trade. They were early taught that the Hudson Bay Company was a great benefactor and readily conceded its domination. This company was wholly a commercial concern, and in their treatment of the Indians they were simply cherishing the goose that laid the golden eggs. Recognizing the fact that in the course of time the country would be settled by whites who would not be subservient to them, and that education and Christianization of the Indians would be the least objectionable method of approaching the inevitable, they encouraged the coming of missionaries and the establishment of missions. Under the circumstances it was inevitable that the Indians should make a distinction between the missionaries and their followers, and the roaming adventurers who were not subject to the the great company, nor in accord with the missionary sentiment. Ashland Daily Tidings, September 30, 1924, page 2

The importance of the fur trade was early recognized, and the fortunes that were being built up by it aroused the cupidity of others. Moneyed men were at all times ready to invest where the harvest promised such great returns, and plenty of reckless adventurers were ready to brave the dangers of the wilderness for the "fun" and thrill of it under circumstances which promised them uncontrolled liberty and freedom of action. Other organizations were formed, and these adventurers were enrolled for action in the wilderness. Great activity between competing companies soon arrayed the followers of each in antagonisms. Independent trappers not in the employ of the Hudson Bay Company were soon in feuds with the great organization's trappers, and in the conflicts resulting the Hudson Bay trappers had the advantage of Indian support. The Indians soon learned that these independent adventurers were to be discouraged from pursuing their chosen vocation because it antagonized the powers that dominated them and to which they were pledged to fidelity. It was only the exercise of natural human instincts, uneducated, uncivilized and practically uncontrolled, that prompted the attitude of these savages toward all comers not in harmony with the great organization with whom they were related in trade. The trappers who had taken wives among them and had adopted tribal relations conferred among themselves in the interests of the company and, even though the higher-ups of that organization were, perhaps, not directly instigating the savages and often punished them for inhuman acts against the whites, yet their trappers scattered through the wilderness were under no present direction from their employers, and naturally only half-civilized themselves, filled their savage comrades with antipathy against all who were in competition with them. It is not at all strange that these Indians should have been made familiar to a certain extent with white encroachments for many generations back and covering a large part of the American continent. The Indians were also kept informed from the same sources of the coming of those who were to be discouraged because not allied with the Hudson Bay Company. They were also kept informed of the attitude of the United States and Great Britain toward each other on the all-important subject of ownership of the Great Northwest. So we see that from the beginning the Indians were made to understand that it was the wish and aim of the great nation to which the Hudson Bay Company belonged that the American government's claim to the Oregon Territory should be defeated, and they adopted the only methods known to them to aid their great ally. Some people have expressed surprise that Indian tribes at great distances from each other should be kept informed on current events of importance to them. It must be understood that these savage tribes had their own methods of communication, some of which were ingenious and others daring. When white men first came into the country they found a well-traveled trail from the Columbia River to the Sacramento Valley, over which communication was kept up, and from various sources the doings of the outside world were learned. They learned of the war between the United States and Mexico even before Fremont had received his orders to return to California, while he was yet at the head of Klamath Lake in Oregon. The kindness of Dr. McLoughlin, factor of the Hudson Bay Company, toward the early settlers and his encouragement of the establishment of missions in the Willamette and along the Columbia, while recognized as an act of generosity and mercy, was no less an act of statesmanship, but not understood by those above him. The missions established in the Willamette and along the Columbia were clustered about directly under his eye where the inevitable might best be shaped and directed. There were no efforts to establish missions in Southern Oregon, and the first move in that direction by Dr. H. K. Hines in 1834 was discouraged by the Hudson Bay Company's representative stationed on the Umpqua River south of the Calapooia Mountains, and he reported the Indians there to be dangerous and unreliable. Even at the time of Jedediah S. Smith's adventure with the Indians at the mouth of the Umpqua River in 1828, they were not ignorant of the power and importance of the Hudson Bay Company, for Dr. McLoughlin at once took the responsibility to punish them and recover the property they had taken from Smith. These Indians knew about the great power on the Columbia to which they had to bow, and doubtless they had also learned that prowling white adventurers not of that company should be discouraged. The leading chiefs in the subsequent Rogue River Indian Wars were also informed of the feuds among white men that were coming into their country. Ashland Daily Tidings, October 2, 1924, page 2

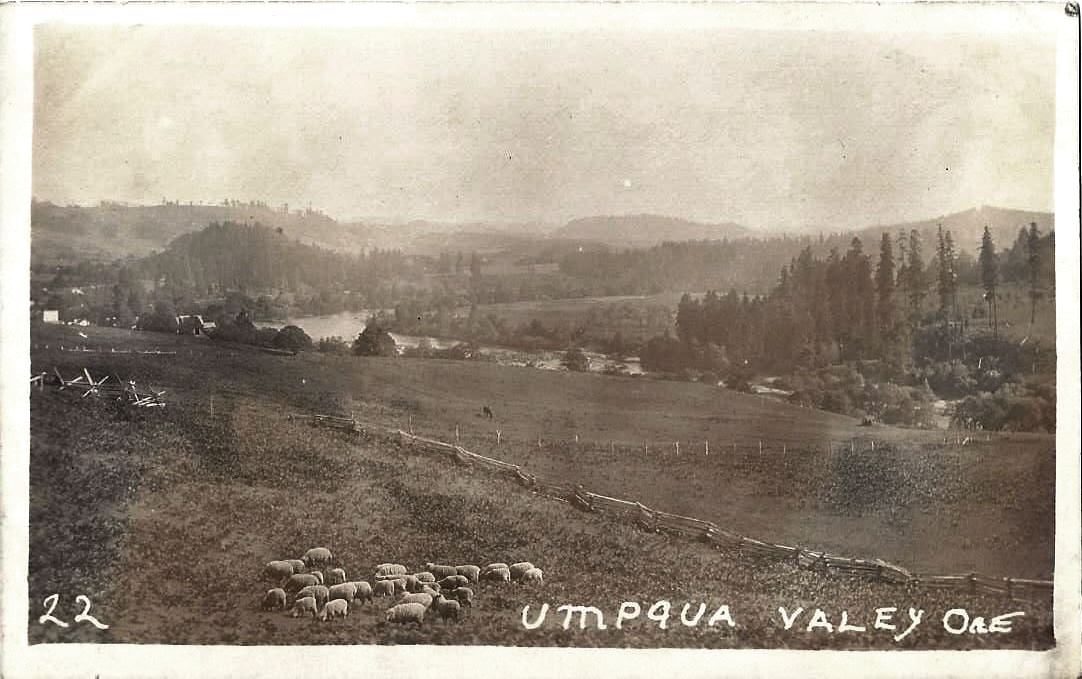

The first great impetus in the settlement of Oregon was given by the immigration of 1843, which came by the way of Fort Hall, Boise and the Columbia River. Walling's history says: "This great train of hardy pioneers who came to Americanize Oregon contained 875 persons, 295 of whom were men over sixteen years of age." On May 2, 1843, the first American government on the Pacific coast was organized at Champoeg, on the Willamette River a few miles below where the capital of the state now stands. At that meeting there were 102 votes cast, and the advocates who favored the stars and stripes carried the day by a majority of two. That fall the "Great Immigration" cited above added nearly one thousand people to the population of Oregon. From this time on, the population increased very rapidly and spread out over the Willamette Valley toward the south until the Calapooia Mountains that separated it from the Umpqua country was reached. Each succeeding year added increasing numbers until in 1846 a party of fifteen men from the Willamette Valley explored the Umpqua country. Among them was Philip Peters, who settled on Deer Creek in 1851. Prior to this, however, in the spring of 1848, Levi Scott with his two sons, William and John, settled in the Umpqua country, Levi Scott at Elk Creek and his sons in the Yoncalla Valley nearby. The next year Jesse Applegate, J. T. Cooper, John Long and _____ Jeffrey settled in the same neighborhood. Prior to all these settlements was that of Warren N. Goodell, who located a claim where the present town of Drain now stands in 1847. Thus was commenced the first settlement in the country south of the Calapooia mountains by common consent belonging to that great expanse of mountains and valleys designated as Southern Oregon. From this beginning the country filled up very rapidly, largely for a time by overflow from the Willamette.  The Umpqua Valley circa 1910. Returning now to the year 1846 we must give narrative to an event that has had a wonderfully stimulating effect upon the growth of the country south of the Umpqua. The immigrant train of 1843 was the first to bring their wagons through to the Columbia River, and they found the trip so hard that the Applegates, who were with that train, concluded that a better route ought to be found further south. Their determination to try for such a route was an act shorn of all selfishness and undertaken with the motive and urgent desire to save the flood of coming immigrants from the horrors they had suffered. Especially had the trip down the Columbia impressed them with the desire to save others from its terrors. In the spring of 1846 a company of fifteen men was organized for the purpose of exploring for a more southerly route from Fort Hall into Oregon. This company consisted of Lindsay Applegate, Jesse Applegate, Levi Scott, John Scott, Henry Bogus, Benjamin Burch, John Owens, John Jones, Robert Smith, Samuel Goodhue, Moses Harris, David Goff, Bennett Osborne, William Sportsman and William Parker. This company was organized in the upper Willamette Valley and after gathering all the information they could they started south through a country notoriously hostile to the white man. The following extract is taken from the diary of Lindsay Applegate, and is quoted so far as to meet the requirements of our present purpose. Quotation follows: "From what information we could gather from old pioneers and the Hudson Bay Company, the Cascade Mountains to the south became very low, or terminated where the Klamath cut the chain; and knowing that the Blue Mountains lay (in a direction) east and west, we concluded that there must be a belt of country extending east toward the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains where there might be no vast, lofty ranges to cross. So in 1846 we organized a company to undertake its exploration, composed of the following persons: (The names are given above.) Each man was provided with a saddle horse and a pack horse, making thirty animals. "A portion of the country we proposed to traverse was at that time marked on the map 'unexplored region.' All the information we could get relative to it was from the Hudson Bay Company. Peter Skene Ogden, an officer of the company, who had led a party of trappers through that region, represented that portions of it were desert-like, and that at one time his company was so pressed for the want of water that they went to the top of the mountain, filled sacks with snow, and were thus able to cross the desert. He also stated that portions of the country through which we would have to travel were infested by fierce and warlike savages, who would attack every party entering their country, steal their traps, waylay and murder the men, and that Rogue River had taken its name from the character of the Indians inhabiting its valleys. The idea of opening a wagon road through such a country at that time was scouted as preposterous. These statements, though based on facts, we thought might be exaggerated by the Hudson Bay Company in their own interest, since they had a line of forts on the Snake River route, reaching from Fort Hall to Vancouver, and were prepared to profit by the immigration. One thing which had much influence with us was the question as to which power, Great Britain or the United States, would eventually secure a title to the country, [which question] was not settled, and in case war should occur and Britain prove successful, it was important to have a way by which we could leave the country without having to run the gantlet of the Hudson's Bay Company forts and falling a prey to Indian tribes which were under British influence." Ashland Daily Tidings, October 4, 1924, page 2

"June twentieth, 1846, we gathered on the La Creole, near where Dallas now stands, moved up the valley and encamped for the night on Mary's River, near where the town of Corvallis has since been built. "On June twenty-third, we moved on through the grassy oak hills and narrow valleys to the North Umpqua River. The crossing was a rough and dangerous one, as the riverbed was a mass of loose rocks, and as we were crossing our horses occasionally fell, giving the riders an occasional ducking. "On the morning of the 24th, we left camp early and moved on about five miles to the south branch of the Umpqua, a considerable stream probably sixty yards wide, coming from the eastward. Traveling up that stream almost to the place where the old trail crosses the Umpqua Mountains, we encamped for the night opposite the historic Umpqua Canyon. "The next morning, June 25th, we entered the canyon, followed up the little stream that runs through the defile for four or five miles, crossing the creek a great many times, but the canyon becoming more obstructed with brush and fallen timber, the little trail we were following turned up the side of the ridge where the woods were more open, and wound its way to the top of the mountain. It then bore south along a narrow backbone of the mountain, the dense thickets and the rocks on either side affording splendid opportunities for ambush. A short time before this, a party coming from California had been attacked on this summit ridge by the Indians, and one of them had been severely wounded. Several of the horses had also been shot with arrows. Along this trail we picked up a number of broken and shattered arrows. We could see that a large party of Indians had passed over the trail traveling southward only a few days before. At dark we reached a small opening on a little stream at the foot of the mountain on the south, and encamped for the night. "On the morning of the 26th, we divided our forces, part going back to explore the canyon, while the remainder stayed to guard the camp and horses. The exploring party went back to where we left the canyon on the little trail the day before, and returning through the canyon, came into camp after night, reporting that wagons could be taken through. "Making an early start we moved on very cautiously. Whenever the trail passed through thickets we dismounted and led our horses, having our guns in hand, ready any moment to use them in self-defense, for we had adopted this rule, never to be the aggressors. Towards evening we saw a great many Indians posted along the mountainside, and now and then running ahead of us. As we advanced toward the river (Rogue River), the Indians in large numbers occupied the riverbank near where the trail crossed. Having understood that this crossing was a favorite place of attack, we decided, as it was growing late, to pass the night in the prairie. "In selecting our camp on Rogue River, we observed the greatest caution. Cutting stakes from the limb of an old oak that stood in the open ground, we picketed our horses with double stakes as firmly as possible. The horses were picketed in the form of a hollow square, outside of which we took up our positions. We kept vigilant guard during the night, and the next morning could see the Indians occupying the same position as at dark. There had been a very heavy dew and fearing the effect of dampness on our firearms, which were muzzle-loaders, of course, and some of them with flintlocks, we fired them off and reloaded. In moving forward we formed two divisions with the pack horses behind. On reaching the riverbank the front division fell behind the pack horses and drove them over, while the rear division faced the brush, with guns in hand, until the front division was safely over, then they turned about, and the rear division passed under the protection of their rifles. The Indians watched the performance from their places of concealment, but there was no chance for them to make an attack without exposing themselves to our fire. The river was deep and rapid, and for a short distance some of the smaller animals had to swim. Had we rushed pell-mell into the stream, as parties sometimes do under such circumstances, our expedition would probably have come to end there." (This crossing was a short distance above where Grants Pass now is.) "After crossing we turned up the river, and the Indians in large numbers came out of the thickets on the opposite side and tried in every way to provoke us. There appeared to be a great commotion among them. A party had left the French settlement in the Willamette some three or four weeks before us, consisting of French half-breeds, Columbia Indians and a few Americans; probably about eighty in all. Passing one of their encampments we could see by the sign they were only a short distance ahead of us. We afterwards learned that the Rogue Rivers had stolen some of their horses and that an effort to recover them had caused the delay. From our camp we could see numerous signal fires on the mountains to the eastward." Ashland Daily Tidings, October 6, 1924, page 2

"Spending most of the day in examining the hills about the stream now called Keene Creek, near the summit of the Siskiyou ridge, we moved on down through the heavy forest of pine, fir and cedar, and camped early in the evening in a little valley now known as Round Prairie. On the morning of July first, being anxious to know what we were to find ahead, we made an early start. This morning we observed the track of a lone horse leading eastward. Thinking it had been made by some Indian horseman, we undertook to follow it. This we had no trouble in doing, as it had been made in the spring, while the ground was damp, and was very distinct, until we came to a very rough, rocky ridge, where we lost it. "On July third, we appeared to have found a practical pass and camped in a small, rich, grassy valley through which ran a small stream. This valley is now known as Long Prairie. After crossing the summit of the Cascade ridge, the descent was in places very rapid. At noon we came out into a glade where there was water and grass and from which we could see the Klamath River. After noon we moved down through an immense forest, principally of yellow pine, to the river; thence up along the north bank of the river, through this splendid forest for several miles when we crossed the stream at some rapids, just below where the present village of Keno stands. From higher ground here, the party had a splendid view of the Lower Klamath lakes, swamps and country." The narrator says: "It was an exciting moment, after the many days spent in the dense forests and among mountains, and the whole party broke forth in cheer after cheer." We will have occasion to travel more with these adventurers in their effort to find a more suitable route into Oregon, and will see them leading the first wagon train that ever invaded Southern Oregon. From their crossing of Klamath River they turned south along the west side of the "Lower Klamath Lakes" to its southern extremity, thence easterly around its southern shore to Lost River and the Tule Lake country, where long years afterward were to be enacted that heartbreaking series of tragedies leading up to and terminating with the Modoc War in 1872-3. CHAPTER THREE

The Applegate party continued

their exploration of the southern trail eastwardly to Fort Hall, where

they found a large number of emigrants, which is reported numbered two

thousand people, with 470 teams and 1050 cattle. About half of these

people took the Humboldt route to California in separate trains. Among

them was the ill-fated "Donner party," of whom so many perished from

starvation and exposure on the mountains. The greater part of the

remainder of those gathered at Fort Hall followed the old trail down

the Snake and Columbia rivers, suffering the usual hardships of the

trip. The remainder, consisting of forty-two wagons and one hundred and

fifty people, took the new route with the Applegate pilots. They could

not have dreamed that through that gap across [omission]

northern Nevada for want of water and pasturage until they reached

Goose Lake, after passing which they entered forests interspersed with

glades and here and there grassy valleys and an abundance of water.

From Goose Lake to Tule Lake they had much rough, rocky country to

cross but were not interfered with by the Indians, though, as

subsequent events showed they were passing through a land infested by

the most ferocious savages on the coast. They passed through the "Lower

Klamath Lake country," dodging marshes, passing around lakes and

crossing streams and sloughs in their approach to the Cascade

Mountains, where they entered the great forest that lies between the

Klamath country and Rogue River Valley, after crossing the Klamath

River. They now had about forty miles of this great forest that had

never before been entered with wagons or white families. The immigrants

had become skilled to such problems as they encountered and were guided

by men of courage, humanity and spirit, and at last stood at the last

summit, now known as Green Spring Mountain, and looked into the

beautiful valley of Rogue River.

Ashland Daily Tidings, October 13, 1924, page 2

As they stood on this summit, ragged, weary, perhaps begrimed and travel-stained, what varied emotions must have possessed them. Doubtless they were told that much of the terrors and dangers they had encountered was over. No longer would they be the sufferers from thirst and lack of provender for their stock. Doubtless they were told that the beautiful country spread out below them was infested by bands of thieving and pitiless savages against whom constant vigilance would have to be practiced. Before them was spread a beautiful picture, more inspiring than any they had seen, though all their troubles were not over. It was the first immigrant train that had ever stood on the border of Rogue River Valley and they recorded its charms, a wonderful picture of valley and mountain. Waving grass, groves of oak and madrone with wonderful coloring invited their attention. Before them towered the great Siskiyou Range with its dense forests and to the left a gap through which passed a centuries-old trail, where the moccasin tracks and pony route of Indians had made indelible the historic traffic of savages between the Columbia and the great Mexican province of California, for the possession of which, their own beloved United States, at that moment war was being waged. They had no means of knowing how this great conflict was faring. Could the veil of the future have been torn away, they would have visioned a spectacle that would have seemed a translation to another realm. They could not have realized that the time would come when the forest and mountain through and over which they had just passed would be provided with such a road as they had never dreamed of, a road costing more than a million of dollars, and that their guides were to be the recorded pathfinders and their company was at that moment breaking the spell in the interest of future greatness. They could not have dreamed that through that gap across the Siskiyous would be a great railroad, in plain view from where they stood, engaged in carrying an undreamable traffic for thousands of miles up and down this new, savage coast. They could not have dreamed that winding its sinuous course parallel with the railroad would be a paved highway from British Columbia to Mexico, over which would speed horseless carriages, with unnumbered hosts of human freight at great speed. They could not know that within five years from their advent gold would be discovered in those mountains to the west, and that thousands of miners would flock thither and the rapid settlement of this beautiful valley would quickly follow; nor realize that they were the pioneers of all this greatness. They were looking upon a picture grander than the pencil of the most skilled artist could paint. They could have no conception of the changes that were rapidly to transform this beautiful landscape, nor the human suffering, savage wars and final extermination of the wild bands that then dominated this wonderful region. The natural resources hidden away in the panorama before them were undreamed of, which their coming and that of others to follow would stimulate into discovery. Theirs were to be the first wagon tracks to be made through Rogue River Valley, soon to be followed by development that would startle the world. Their route hence was to be that which the Pacific Highway would follow, that was destined to become historic the conception of following generations. Ashland Daily Tidings, October 18, 1924, page 2

To reach the floor of the valley they had to descend a very steep and rocky ravine now known as Emigrant Creek in memory of their coming. One familiar with this mountain trail cannot well avoid a feeling of astonishment that it was accomplished without serious accident. The writer traveled this trail fifty-two years ago and saw the marks of their enterprise not yet effaced after twenty-six years. He also at that time traversed the great forest along the route traveled by them and marveled at their accomplishment, compassed after many days of strenuous effort. He also made the trip from Klamath Falls to Ashland, over the million-dollar highway, a few months ago by automobile in two hours and fifteen minutes. It is noted with satisfaction that a granite monument has been erected on the line of this trail [in Phoenix], to the memory of these pathfinders, many of whom afterwards sought homes in this valley. This party was piloted through to the Willamette Valley by these intrepid men, but not without serious adventures of various kinds. At what is known as the Umpqua Canyon, through which the Pacific Highway now passes, their troubles were greatest. Some of the teams had to be rested up there, and great difficulty and hardship was suffered. This canyon was afterwards selected for the stage road from Sacramento to Portland; those of us who traveled by stage over this route twenty-five or thirty years after the passage of this emigrant train took off our hats to their courage and enterprise. I have devoted considerable space to this event, because I consider it to have been of the greatest moment in the settlement of Southern Oregon. It must be remembered that at the time this southern route was sought the question as to whether the United States or Great Britain should hold supremacy over the Oregon Territory was not yet settled, though then in the throes of arbitrament. The Hudson Bay Company had a line of forts, or posts, between Fort Hall and the Columbia River and derived quite a revenue from the immigrants, whose wants they supplied at their own prices. The route was excessively hard, making for the frequency of wants to be supplied. There was much prejudice among the settlers against the company; though Dr. McLoughlin was their benefactor and friend, other officers of the company were not in sympathy with his sentiments of generosity and mercy. These officers and men, stationed at great distances from the headquarters at Vancouver and responding to the opposite feeling of the higher-ups, and in an effort to discourage settlement from the United States in order to further the plans of Great Britain, were charged with making the hardships of the immigrant greater, even to incitement of hostility by the natives. Be this as it may, these feelings prompted them to engage in counter moves. As I have before said, it is not my intention to rewrite the intensely interesting accounts of the early immigrants to the Columbia and Willamette valleys, because that has been eloquently and at great labor and expense given in the excellent publications and histories already extensively distributed. My excuse for this writing is that the settlement of all that country south of the Willamette Valley was made under circumstances entirely different from that further north. It was not done by missionaries nor trappers and hunters, and being at a distance from the great communities of the Willamette, [it] has not, it seems to me, received the attention that the magnitude and importance of this great area is entitled to. It is not my intention to criticize, or to complain, but rather to complement and extend to the world information of that portion of Oregon south of the Calapooia Mountains. From what has already been said, it will be understood that the Hudson Bay Company operated among the Indians in a manner not to arouse their suspicions. They did not want the Indian lands, nor did they assume to build up exclusive communities which required the land for tillage and home-building, the very fact of which necessarily encroached upon what Indians claimed to be their inalienable rights. The trappers assimilated with the Indians, married Indian women and lived the same kind of life they did. But it was not so with the white settler who came accompanied by his own family, settled on a piece of land, called it his own and refused association with the red men. These native sons were proud and, in their way, intelligent. They were informed of how the countries east of the Rocky Mountains had been appropriated and the Indians gradually driven out, or onto reservations. Of all this they were not ignorant and naturally reasoned that the wedge was being driven by the home builder that must, inevitably, result as it had elsewhere. The missionaries came declaring their purpose to Christianize the Indians; to teach him how to live, how to build homes and how to enjoy life according to the precepts of the Holy Master. That sounded good, but when they found that their methods of life were to be changed and that instead of enjoying a free and untrammeled existence, they were required to work, till the ground and imitate the whites in building homes, and further when they found that white men with their families were coming into the wake of the missionary, assuming superiority over them, they naturally became restless, drew aloof and finally began war upon them. These missions and attended settlements were in the Willamette Valley and along the banks of the Columbia. Most of the histories deal chiefly with these communities and conditions; south of the Calapooia Mountains no missions were established, and with the exception of mining industries, the settlements of Southern Oregon were exclusively of the home-building type, a fact sufficient to arouse the full determination of the savages to drive them hence. Ashland Daily Tidings, October 27, 1924, page 2

This fact being fully understood, we will address ourselves in this volume first to the Indian wars and then to the civil and political growth of the country. This plan, I take it, will be less confusing and give continuity to our story as we proceed. The only serious thought of establishing a mission south of the Calapooia Mountains was by Rev. Jason Lee, who in company with Gustavus Hines visited the Umpqua River in 1840. The party consisted of Rev. Jason Lee, Rev. Gustavus Hines, Dr. Elijah White and an Indian guide, whom they called "Captain." They started from the mission a few miles below where Salem now stands and proceeded up the Willamette River, camping where night overtook them and meeting with no mishap, and on the third day passed over the Calapooia Mountains at the pass where the railroad now crosses and came down the south side to Elk Creek where the California trail crossed it. This is where Drain now stands. At this point they left the California trail and turned west along Elk Creek. They described the way as exceedingly rough and mountainous. One acquainted with Elk Creek Canyon is not surprised at this. That afternoon, being August 22nd, they reached the Umpqua River at the mouth of Elk Creek. On the opposite side of the river stood the Hudson Bay Company's fort, or trading station. They crossed over in a canoe and were kindly received by an old Frenchman having charge of the post. The name of this man was Goniea. [Jean Baptiste Gagnier operated Fort Umpqua.] Of him, Rev. Hines says: "The Frenchman in charge, it is said, belongs to a wealthy and honorable family in Montreal, and though frequent efforts have been made to reclaim him from his wanderings and induce him to return to his family and friends, yet all have been unavailing. Such is the power of habit with him that he now prefers a life but little in advance of the wretched savages that surround him, to all the elegances and refinement of a most civilized society. He lives with an Indian woman whom he calls wife, and who belongs to the tribe that resides on the coast, near the mouth of the Umpqua River." Dr. White and the Indian guide returned to the Willamette and Rev. Hines and Lee prepared to make the trip to the mouth of the river. The Frenchman tried to dissuade them from going alone, telling them that they would be in great danger in going among them alone and himself appeared to be in utmost fear of them. Hines says: "Of their hostility to the whites, and especially to the Americans, we were ourselves aware." He then narrates the Jedediah Smith affair in which eleven men were massacred at the mouth of the river some years before, to which reference has heretofore been made. A small party from down the river arrived in the evening, among whom was a brother of the Frenchman's squaw. After talking with them, Rev. Hines and Lee proposed to the Frenchman that his squaw, her and her brother accompany them in their contemplated trip to the coast. To this the Frenchman consented, saying, "Now the danger is small, before it was great." The next morning they accompanied the Indians in canoes and camped one night before reaching their destination. They were lulled into a sense of security by the meek and lowly appearance of the Indians, who were represented as disgustingly filthy and degraded. They held divine services, to which they fancied the Indians responded with a sincere desire for instruction. They remained two nights, during which they noticed that the Frenchman's squaw and her brother remained up all night and kept a bright fire burning between the camp of the missionaries and that of the Indians, which had been established some little distance apart. They did not, at the time, know why this fire had been kept burning, but after returning to the Frenchman's post up the river they were informed that the plan of the Indians the evening before was to murder them that night, and doubtless would have done so had not these two proved true to their duty. While still at the post their apprehensions were further aroused and they concluded to return to the Willamette and abandon further effort. They felt themselves in great danger from treachery and suffered much from exposure and indignity of the Indians before they reached the California trail. Of the character of these Indians we will let Rev. Hines tell us. He says: "Notwithstanding the seeming favor with which we were received by them, the Indians along this river, and especially those along the coast, have often proved to be among the most treacherous of savages, and none have ever been among them but have learned that they are capable of practicing the most consummate duplicity. A story told by the gentlemen of the Hudson Bay Company, concerning what transpired on this river, clearly illustrates the treachery and cruelty of these savages, as well as the perilous adventures of the Oregon mountaineers." The narrator then proceeds to give the story of the massacre of Jedediah Smith's company at the mouth of the river in 1828, a portion of which narrative is as follows: "The country was in its wildest state, but few white men ever having passed over it. But nothing daunted, Smith and his company marched through California and thence along the coast, north as far as the Umpqua River, collecting in their progress all the valuable furs they could procure, until they had loaded several pack animals with the precious burden. On arriving here they camped on the border of the river, near the place where they intended to cross, but on examination found that it would be dangerous, if not impossible, to effect the passage of the river at that place. Accordingly Smith took one of his men and proceeded up the river on foot, for the purpose of finding a better place to cross. In his absence the Indians, instigated by one of the savage-looking chiefs whom we saw at the mouth of the river, rushed upon the party with their muskets, bows and arrows, tomahawks and scalping knives, and commenced the work of death. From the apparent kindness of the Indians previously, the party had been thrown entirely off their guard, and consequently were immediately overpowered by their ferocious enemies, and but one of the twelve in camp escaped the cruel massacre. "Scarcely knowing what to do he fled and fell in with Smith, who was on his return to the camp, and who received from the survivor the shocking account of the murder of eleven of his comrades. Smith, seeing that all was lost, resolved to attempt nothing further than securing his own personal safety and that of his two comrades, the Indians having secured all the fur, horses, mules, baggage and everything the company had. The three immediately crossed the river and made the best of their way through a savage and inhospitable country towards Vancouver, where after traveling between two and three hundred miles, and suffering the greatest deprivation, they finally arrived in safety." "After learning the details of the massacre of the Smith party and observing the degraded and treacherous character of these Indians, no further effort to establish a mission south of the Calapooia Mountains was attempted. These stories were known throughout the Willamette Valley and for the time discouraged thoughts of settlements in the Umpqua country. Doubtless the returning Applegate party with the first train over the southern route were also made familiar with the dangerous character of the natives of this region and could feel no assurance of safety until they had passed this hostile and treacherous tribe. Ashland Daily Tidings, November 3, 1924, page 7

CHAPTER FOUR

The

uncertainties involved in the ultimate settlement of the Oregon

question bring the southern trail into more general consideration

The year of 1846 was in many ways a year presenting many serious questions. The settlement of the "Oregon question" was the most pressing of all subjects for public and private discussion. In the case of war between the United States and Great Britain, it was seen that there must be some route to and from the "Oregon country" other than that which followed the Hudson's Bay line of trading posts and forts, over which up to this time the immigrants found their only route to travel. The United States would not be likely to select a line already occupied and fortified by its enemies in the event that military forces were to be sent out. Hence, this southern route was anxiously looked upon as the most available for the future needs of the country. The new route was not in every respect as good as it was hoped to find, but it was believed that with more intimate acquaintance it would be found to present less of hardships than the Snake and Columbia rivers route. Besides, Oregon would be reached earlier in its southern valleys, that were in some respects more inviting to the weary immigrant. When these first pioneers had seen Rogue River and Umpqua valleys, they ceased not to discuss their desirability when they had reached the settlements of the Willamette, and many of them in subsequent years returned to make their homes there. Jealousies between the various missions and the various denominations that fostered them produced dissensions that were carried into politics in the early efforts to establish a provisional government, which added to their other embarrassments and discredited them in the eyes of the Indians, who soon were made aware of the situation. The missionaries soon became discouraged in their efforts to "Christianize" the Indians and lost morale when they discovered the difficulties that confronted them. It is not strange that under the circumstances stimulus was added to the efforts of those who championed the Applegate route. Bancroft says: "In May 1847, Levi Scott led a party of twenty men destined for the States over the southern route, and also guided a portion of the immigration of the following autumn into the Willamette Valley by this road, arriving in good season and good condition, while the main immigration, by the Dalles route, partly on account of its number, suffered severely. This established the reputation of the Klamath Lake road, and the legislature this year passed an act for its improvement, making Levi Scott commissioner, and allowing him to collect a small toll as his compensation for his services. The troubles with the Cayuses which broke out in the winter of 1847 and which, but for the Oregon volunteers, would have closed the Snake route, demonstrated the wisdom of its explorers in providing the mountain-walled valleys of western Oregon with another means of ingress or egress than the Columbia River, their road today being incorporated in some way with some of the most important highways of the country. "In June 1847, a company headed by Cornelius Gilliam set out with the intention of exploring the Rogue River and Klamath valleys, which from this time forward continued to be mentioned favorably on account of their climate, soil and other advantages. "In 1849 Jesse Applegate removed to the Umpqua Valley, at the foot of a grassy butte called by the Indians 'Yone-calla, or eagle-bird,' which use has shortened to 'Yoncalla,' near Elk Creek, close to which the railroad now passes. His brother Charles settled nearby him, and Lindsay Applegate somewhat later made himself a home on Ashland Creek, where the town of Ashland now stands, and directly on the line of the road he helped to establish." "Uncle" Lindsay Applegate told the writer fifty years ago that after he had received his first view of Rogue River Valley on that memorable trip of 1846, he had declared a vow that he would sometime make a home here, and up to the date of his death he considered Rogue River Valley the gem of the Pacific coast. The year 1846 was a memorable one in the annals of the Pacific coast; the treaty with Great Britain was ratified, fixing the boundary line at the 49th parallel north. This gave the U.S. all that territory known as Old Oregon, extending from the Pacific Ocean to the summit of the Rocky Mountains, and from the 42nd to the 49th parallel of north latitude. This removed the menace of war that had so long hung over this region, and gave the anxious settlements promise of speedy protection under the stars and stripes. The same year saw California a possession of the United States, an unbroken coast line from Mexico, at the head of the Gulf of California to the 49th degree of north latitude. The immigration was increasing each year at a rapid rate, and an added impetus was given by this new assurance of protection. From this time on exploration of this immense empire of territory went on rapidly, and the country south of the Calapooia Mountains commenced to receive homeseekers. In 1847 Warren N. Goodall located a donation claim on the present site of Drain, at a point where the present S.P. railroad crosses Elk Creek. In 1848 Levi Scott settled in Scott Valley near the mouth of Elk Creek, and his two sons, William and John, settled nearby in Yoncalla Valley. In 1848 Jesse Applegate, J. T. Cooper and _____ Jeffrey settled in the same vicinity. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 had attracted great attention in all parts of California and Oregon, and induced an increase in the travel over the California trail in great numbers, of which we will speak more particularly presently, and new settlements were begun in the Umpqua Valley. Bancroft says: "The immigration to the Pacific coast in 1850, by the overland route alone, amounted to between thirty and forty thousand persons, chiefly men. Through the exertions of the Oregon delegate in Congress about eight thousand were induced to settle in Oregon." With the yearly increase since the large immigration of 1843, with eight thousand added in 1850, Oregon was securing a population able to cope with emergencies as they arose and were no longer uncertain as to their national status, having been given a territorial government in 1849. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 produced a remarkable situation wherever the news spread. Perhaps nowhere else in the world was there wrought a greater spectacle than in Oregon. These pioneers who had just arrived and yet had hardly settled on the lands chosen by them were violently taken with the lust for gold. So soon as the news was fully confirmed and verified that the reported discovery was not a hoax, the greatest excitement prevailed. We will let Bancroft paint the picture for us. He says: "No one doubted longer; covetous desire quickly increased to a delirium of hope. The late Indian disturbances were forgotten, and from the ripening harvests the reapers without compunctions turned away. Even their beloved land claims were deserted; if a man did not go to California it was because he could not leave his family or business. Some prudent persons, at first seeing that provisions and lumber must rapidly increase in price, concluded to stay at home and reap the advantage without incurring the risk; but these were a small proportion of the able-bodied men of the colony. Far more went to the gold mines than had volunteered to fight the Cayuses; farmers, mechanics, professional men, printers--every class. Tools were dropped and work left unfinished in the shops. The farms were abandoned to women and boys. The two newspapers, the Oregon Spectator and Free Press, held out, the one till December, the other till the spring of 1849, when they were left without compositors and suspended. No one thought of the outcome. It was not then known in Oregon that a treaty had been signed by the United States and Mexico, but it was believed that such would be the result of the war; hence the gold fields of California were already regarded as the property of Americans. Men of family expected to return; single men thought little about it. To go and go at once was the chief idea. Many who had not the means were fitted out by others who took a share in the venture; and quite different from those who took like risks in the East, the trusts reposed in men in Oregon were as a rule faithfully carried out." Ashland Daily Tidings, November 4, 1924, page 2

"Pack trains were [at] first employed by the gold seekers; then in September a wagon company was organized. A hundred and fifty robust, sober and energetic men were soon ready for the enterprise. The train consisted of fifty wagons loaded with mining implements and provisions for the winter; even planks for the construction of gold rockers were carried in the bottom of some of the wagons. The teams were strong oxen; the riding horses of the hardy Cayuse stock, late worth but ten dollars, now bringing thirty, and the men were armed. Burnett was elected captain and Thomas McKay pilot. They went to Klamath Lake by the Applegate route, and then turned southeast, intending to get into the California emigrant road before it crossed the Sierra. "The exodus thus begun continued as long as weather permitted, and until thousands had left Oregon by land and sea. The second wagon company of twenty ox teams and twenty-five men from Puget Sound followed but a few days behind the first, while the fur-hunters' trail west of the Sierra swarmed with pack trains all the autumn. Their first resort was Yuba River, but in the spring of 1849 the forks of the American became the principal field of operations, the town of Placerville, first called Hangtown, being founded by them. They were not confined to any localities, however, and made many discoveries, being for the first winter only more numerous in certain places than other miners, and as they were accustomed to camp life, Indian fighting and self-defense generally, they obtained the reputation of being clannish and aggressive. If one of them was killed or robbed, the others felt bound to avenge the injury, and the rifle, or the rope, soon settled the account. Looking upon them as interlopers, the Californians naturally resented these decided measures. But as the Oregonians were honest, sober and industrious, and could be accused of nothing worse than being ill-dressed and unkempt and of knowing how to protect themselves, the Californians manifested their prejudice by applying to them the title of 'lop ears,' which led to the retaliatory appellation of 'tar heads,' which elegant terms long remained in use. "It was a huge joke, gold mining and all, including even life and death. But as to rivalries they signified nothing. Most of the Oregon and Washington adventurers who did not lose their lives were successful; opportunity was greater there in the Sierra foothills than in the Willamette Valley. Still they were not hard to satisfy, and they began to return early in the spring of 1849, when every vessel entering the Columbia River was crowded with home-loving Oregonians. A few went into business in California. The success of those that returned stimulated others to go who at first had not been able." A complete revolution in business, hope, ambition and all of the sentiments and aspirations that these new settlers had almost lost in discouragement from their overland trip and the wild surroundings of their new home, now returned to them increased manifold, and progress that they had not before dreamed of forged to the forefront. Immigration to this new Eldorado increased to an amazing extent. The statesmen in the East lost tongue longer to disparage the future of the great Northwest, and a territorial government was at once forthcoming. The Columbia River was the scene of great activity, and ships from all parts of the world swarmed its waters. Cities and towns sprang up everywhere, supported by an intelligent growth of agriculturists. Great farming communities were soon bidding for the markets of the world, and the salubrity of their climate and fertility of their soil demonstrated the wisdom of their choice and enhanced the world's opinion of the coming greatness of the United States. The miners of California at once became the most important bidders for the produce of Oregon, and the ships sailed for the Columbia to bear it to them. The General Lane sailed from Oregon City with lumber and provisions, and had on board several tons of eggs which had been purchased at the market price and sold to a passenger at thirty cents a dozen, who sold them at Sacramento for a dollar apiece. The large increase of home productions with the influx of gold by the returning miners soon enabled the farmers to pay off their debts and improve their places, a labor upon which they entered with ardor in anticipation of the donation law. In the spring of 1849 many more went to the mines and many more who had been there returned, and the California trail through Southern Oregon became well known. Those who went overland to California returned to their homes in the Willamette to sound the praises of the beautiful Umpqua and Rogue River valleys. It is not at all strange that such large numbers of white people passing back and forth through this region, where only two or three years before a white man was rarely ever seen, should cause excitement and apprehension among the natives. The Indians also soon learned that the United States, and not Great Britain, had been awarded the great Northwest, and that their friends, the Hudson Bay Company, were no longer supreme authority. The discovery of gold also both hurt and helped the Hudson Bay people. Many of the trappers abandoned their fur-hunting haunts and rushed to the mines. In fact, the gold hunting delirium tended for the time being to unsettle everybody and everything. Returning miners were often waylaid by the savages as they passed through Rogue River Valley and the Umpqua and robbed of their treasures, sometimes killed. This gold excitement in California spread like a plague, and within a year prospectors had followed up the Sacramento River looking for gold and often finding it. The Oregon miners returned from California, scanned the mountains and gulches, and prospected as they went along. They noticed that the formations and general structure of the country about Trinity Mountains, Scotts Mountains and the Siskiyou Mountains seemed much the same as that in the Sierras where they had worked the rich deposits. Bancroft says that: "In June 1850, two hundred miners were at work in the Umpqua Valley. But little gold was found at that time, and the movement [was] southward, to Rogue River and Klamath. According to the best authorities, the first discovery of any of the tributaries of the Klamath was in the spring of 1850, at Salmon Creek. In July discoveries were made on the main Klamath, ten miles above the mouth of the Trinity River, and in September on the Scott River. In the spring of 1851, gold was found at various places, notably on Greenhorn Creek, Yreka and Humbug." It was not long until these discoveries had attracted many miners, and the mountains in that region were swarming with prospectors and miners. At that time the region was isolated, with hundreds of miles between these camps and San Francisco and Sacramento, their base of supplies, and speculators were being attracted toward the possibilities opening up for methods of transportation to the mines. A vague, indefinite notion existed as to the mouth of the Klamath River as a possible place for vessels to discharge cargo to be conveyed overland to the mines on the Klamath. Ashland Daily Tidings, November 5, 1924, page 2

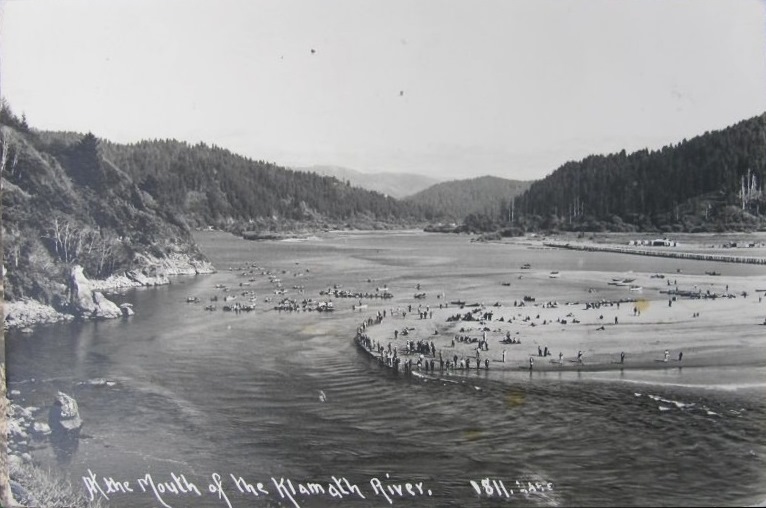

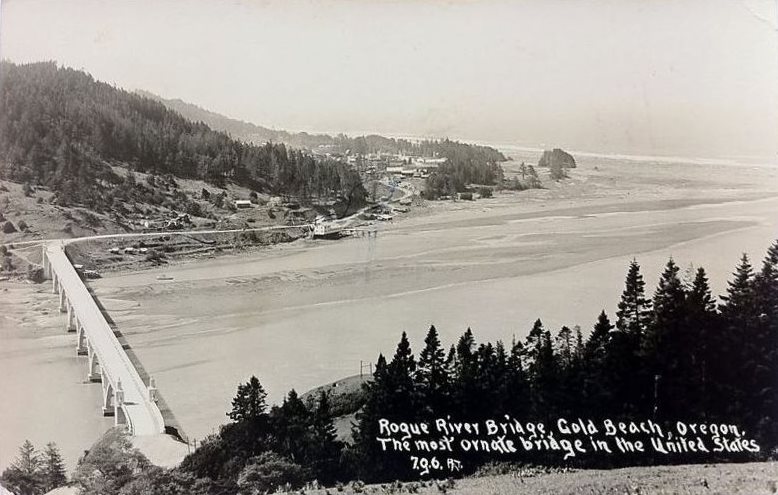

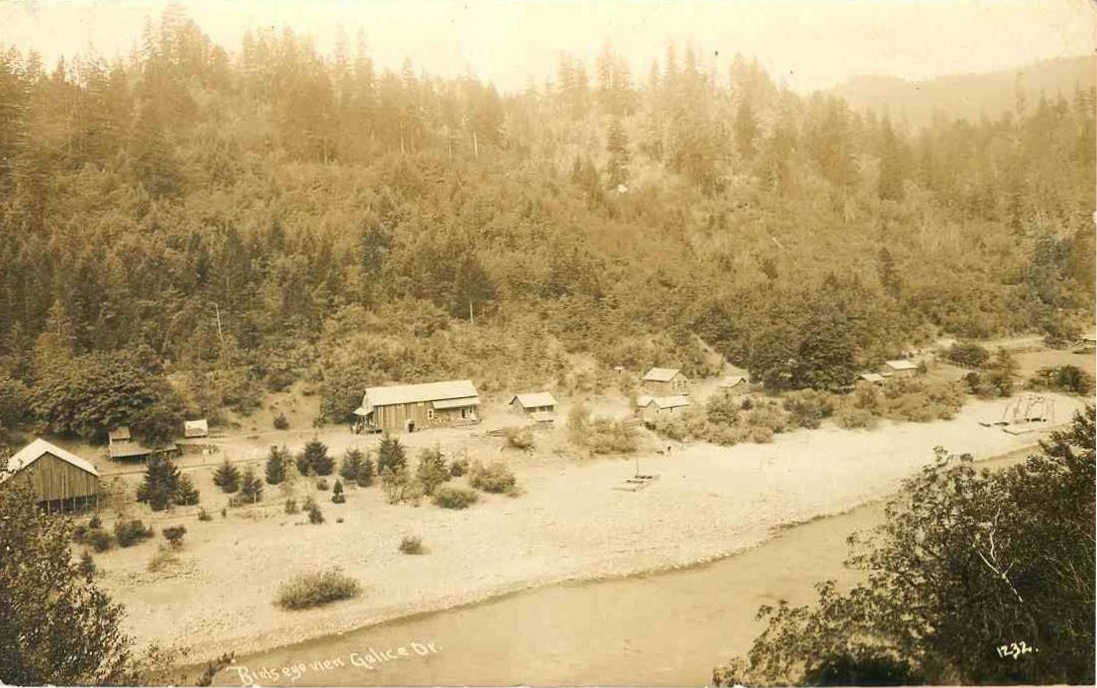

The mouth of the Klamath River, circa 1910. Again we will have recourse to Bancroft's works; speaking of this period he says: Under the excitement of gold-seeking and the spirit of adventure awakened by it, all the great northwestern seaboard was opened to settlement with marvelous rapidity. A rage for discovery and prospecting possessed the people, and produced in a short time marked results. From the Klamath River to Puget Sound, and from the upper Columbia to the sea, men were spying out mineral wealth or laying plans to profit by the operations of those who preferred the risks of the gold fields to other and more settled pursuits. In the spring of 1850 an association of seventy persons was formed in San Francisco to discover the mouth of the Klamath River, believed at that time * * * to be in Oregon. The object was wholly speculative, and included besides hunting for gold the opening of a road to the mines of northern California, the founding of towns at the most favorable sites on the route, with other enterprises. In May thirty-five of the shareholders and some others set out in the schooner Samuel Roberts to explore the coast near the Oregon boundary."  The mouth of Rogue River, circa 1930s. The pursued their course up the coast, passing Coos Bay, which on account of failure of the wind they could not enter, and while becalmed they were approached by a canoe containing Umpqua Indians who offered to pilot them to their river, the Umpqua. Their offer was accepted and they reached the entrance on the 5th of August. On the 6th the schooner crossed the bar, being the first vessel known to have entered the river in safety. They rounded into a cove, since known as Winchester Bay, and were surprised to meet a party of Oregonians, consisting of Levi Scott, Jesse Applegate and Joseph Sloan, who were themselves exploiting [exploring?] the valley of the Umpqua for a purpose similar to their own. A boat was sent ashore and a joyful meeting took place in which each party promised mutual assistance to the other. It was found that Scott had already taken a claim about twenty-six miles up the river at a place which is now known as Scottsburg and which was destined to have quite a history in the early development of the country. Scott, Applegate and Sloan had come down to the mouth of the river in expectation of meeting the U.S. surveying schooner Ewing in the hope of obtaining a good report of the harbor. But on learning the designs of the California company, a hearty cooperation was offered upon the one part and accepted by the other. It seemed that the Indians of the Umpqua had become peaceable and was no longer a menace to the contemplated settlement of the country, which had already begun as shown in prior pages of this history. On the morning of the 7th the schooner proceeded upstream and the bluffs on either hand echoed the joy of the happy party. They ran aground on a sandbar and had to await the tide, but finally reached Scottsburg, the head of tide navigation. The schooner was later brought up. In consideration of their services in opening up the river to navigation and commerce Scott presented the company with one hundred and sixty acres of his land claim, lying below the rapids, for a town site. Affairs now seemed to call for a more regular organization, and a joint stock company was formed and christened the "Umpqua Town Site and Colonization Land Company," the property to be divided into shares and drawn by lot among the original members. They divided their forces and aided by Applegate and Scott proceeded to survey and explore to and through the Umpqua Valley. The company was divided into three parts. One set out for the ferry on the north branch of the Umpqua, the point where the California trail crossed it. Another party accompanied Applegate to Yoncalla, where he had located as hereinbefore told, and the third party left with the schooner. They selected four town sites; one at the mouth of the river was named Umpqua City and contained 1280 acres, being situated on both sides of the entrance. The second location was Scottsburg; the third, called Elkton, was situated on Elk Creek, at its junction with the Umpqua. The fourth at the ferry above mentioned was named Winchester, was purchased from the original locator, John Aiken. This was considered a valuable property. After the organization of Douglas County it became for a time the county seat. At the time of this writing the S.P.R.R. company's road crosses the river at this point, and the Pacific Highway also crosses here on a magnificent concrete bridge recently dedicated with lavish ceremony. The entry of this vessel into the Umpqua, the organization following and the advertising which resulted gave a great impetus to the settlement of the Umpqua Valley, and settlers began to crowd over from the Willamette Valley, and the settlement of Southern Oregon was fairly begun. That the Umpqua could be navigated to Scottsburg was heralded over the country and was selected as the point from which supplies could most easily be shipped into the mines of northern California, which were proving very rich and were more easily reached by the gold seekers of the Willamette Valley. By this time more attention was given by prospectors to the country on the north side of the Siskiyou Mountains. In the spring of 1851, the discovery of gold was proclaimed at Big Bar on Rogue River and at Josephine Creek. Both of these localities are within the present boundaries of Josephine County. Packers were now engaged in transporting supplies into northern California by pack trains over the old California trail, and resting their stock in the beautiful, grassy and well-watered Rogue River Valley, through the center of which their pack trains were driven. It was a splendid place to rest and recruit after the arduous work of negotiating about 300 miles of rough mountain trail, through a country infested by thieving tribes of hostile Indians. Many small companies were waylaid and robbed, and sometimes slain, of which we will have more to say during these narratives. Ashland Daily Tidings, November 6, 1924, page 2

In the fall of 1851, James Clugage and J. R. Poole, who were running a pack train from Scottsburg to Yreka, stopped at an inviting cove in the western part of Rogue River Valley to rest up for a few days and while giving their animals needed rest in the splendid natural meadows where the town of Jacksonville now stands, varied the monotony by prospecting the stream that ran through the meadow. As a result they discovered rich placer deposits in what was afterwards called Rich Gulch. They were joined by James Skinner and ______ Wilson and proceeded to open up their claims, which proved to be very rich. This discovery precipitated another mining rush, and it was only a short time until the mountains surrounding Rogue River Valley were filled with miners and prospectors. CHAPTER FIVE

The discovery of rich placer

deposits in the Siskiyou Mountains bordering upon Rogue River Valley,

and on the Klamath River and its tributaries just across the line in

northern California, produced a reenactment in this region of the

exciting inrush of gold-seekers of two years before in the Sierras of

California. In an incredibly short time hundreds of men with pick,

shovel and pan were gathering at the new discovery on Rich Gulch and

Jackson Creek, while hundreds more were seeking out every stream in the

Siskiyous in their mad search for the yellow metal. The Applegate and

its branches, Sucker Creek and its tributaries, the Illinois River and

valley and nearly every bar on Rogue River were soon occupied. The

startled Indians looked on in amazement at what appeared to them a